August 20, 2012 |

BITE: My Journal

Farewell Steven: Letting Go

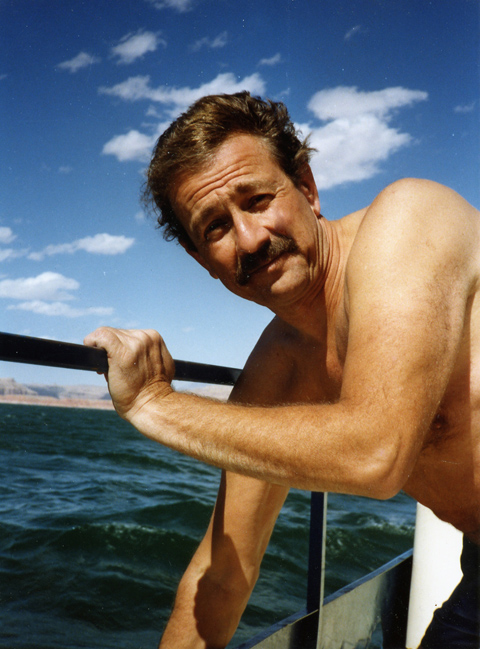

Steven said our time at Lake Powell was his first trip where he wasn’t totally stoned.

What really got me excited about Steven Richter the summer of 1985, in Aspen, was how unrushed he was that first morning after. Men I’d known in the ‘80s had a thousand reasons why they couldn’t spend the night. They couldn’t sleep in a strange bed. They had claustrophobia and it had to be a king size. They had to have a special pillow for their asthma. They needed to get home in case their mother called. They had told their wife they were going out to walk the dog and it was already 45 minutes and she might get suspicious.

Appreciating Steven.

Of course I loved Steven’s looks. The tan, the hippie mustache, that fabulous smile, the top of his brown hair lightened by the sun, the baggy worn jeans, the old tweed jacket. At the bar where a friend brought him to meet me, he was drinking a bottle of Mexican beer, holding it low in front of his crotch…that standup bar posture seemed to be a Western thing. He was born in the Bronx. A mountain man from the Bronx. I liked that. We spoke the same language. I wouldn’t have to learn new folkways. He didn’t say much, but when he did, he was pointed and witty. On our first hike up Hunter Creek, I fell in love with his beautiful lean thighs. And I loved that he taught me how to fall –backwards, on your ass – as if we both knew I was more likely to fall than not.

Aqua Expeditions floating hotel on the Amazon staged cocktails at sunset for us.

Now he lingered for breakfast after the pitiful diet dinner I’d fed him the night before. I thawed a bagel. He liked my coffee. Then he went off to work at the Aspen Art Museum. The next night I gave him a big sirloin, a baked potato and garlic bread. I think he went home seven or eight days later to do the laundry. It seems he lived 20 miles down the road in Basalt, as many working locals did, so I couldn’t take all the credit for his lingering. I went to see his garden. I assured him I knew dozens of recipes for out-of-control zucchini.

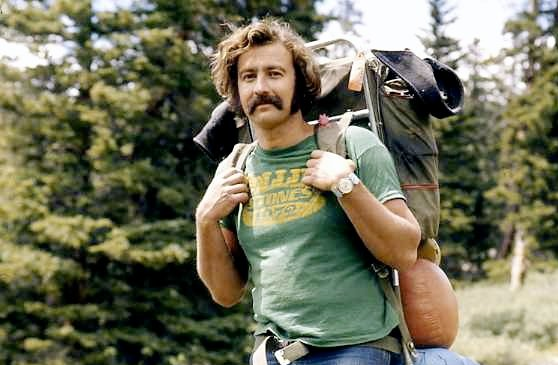

This is the '60s Alaska fire fighter, motorcyclist, Aspen ski bum.

Steven had been lured to Aspen by a ski buddy who urged him to quit his first job after graduation from Cooper Union and discover a skier’s paradise. He worked as a busboy at the Red Onion, then as a bartender, fought fires in Alaska, and criss-crossed the country on a motorcycle.

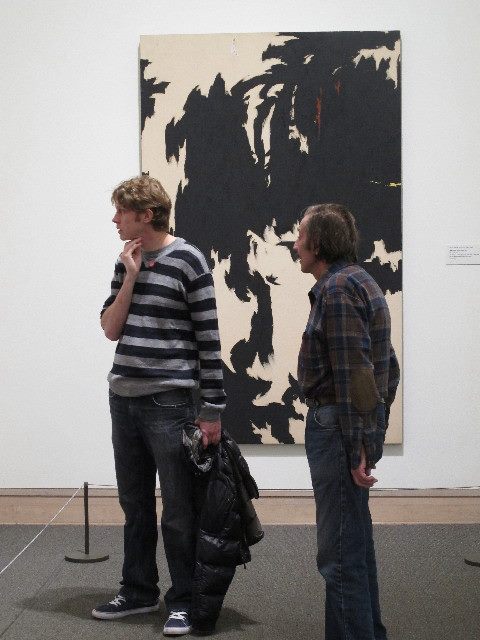

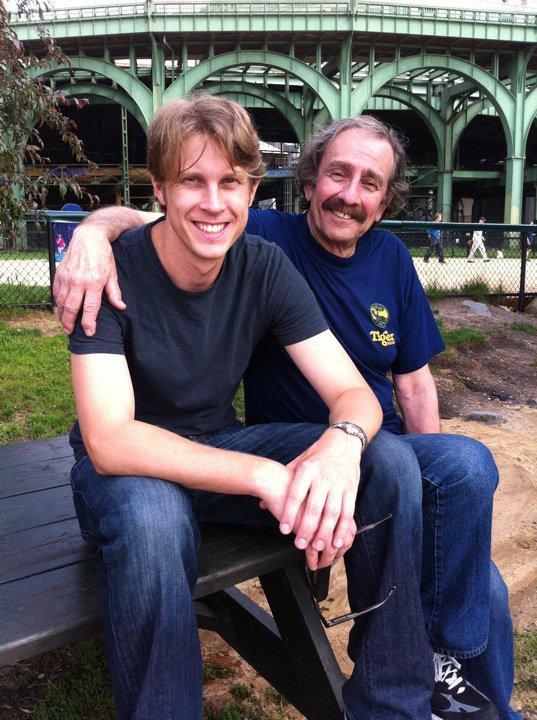

Nico and Steven chilling out in 2008.

For a while he’d go back to New York to teach graphics and make enough money for winter skiing. Then he settled in Aspen, working as a carpenter and contractor with a posse of friends, restoring old Victorian houses, and, on his own, designing and building kitchens. By the time we met, he’d gone on to installing shows and doing graphics at the museum. I remember how pleased he was with his new font for the museum logo. Last week, going through a drawer with his son Nico, we found the t-shirt he designed for the motorcycle show he curated and Nico took it home with him.

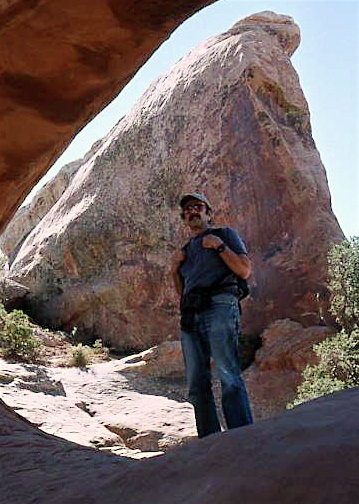

The outdoor loving hiker and camper I just happened to fall for.

We were total opposites. Steven loved the outdoors, hiking, fishing, camping, sleeping out above the timberline. I was a hot-house flower. My sports were sex and dancing. But I thought I should try to be more athletic. I bought some of those tire-tread boots. I signed up for cross-country ski lessons. I thought my strength from years of aerobics would make up for congenital clumsiness and lack of balance. The instructor said he’d never seen anyone less flexible.

Steven was surprised to hear I’d never gone camping. “It’s not because I don’t want to,” I said. “It’s just that people think I’m not the type.” He borrowed a four-wheel-drive truck so we could climb up the pass to Lincoln Gulch, his favorite camping site. He pulled off the trail near a hidden knoll beside a stream and began to unload the tent, a roll-up mattress, down pillows, patchwork quilts, and a bottle of red wine. He handed me potatoes to peel and slice, while he built the fire to grill our steaks in a huge black cast iron skillet. It grew dark and the smell of potatoes frying in butter was dizzying. There were more stars than sky. Underneath my jeans and sweater, I wore a red satin teddy.

A grandmother sells scallions in the Chengdu market. Photo: Steven Richter

I began to commute back and forth to Aspen with research for my New York magazine reviews, carrying one of those huge, heavy, early fax machines, so I had an extra day to make deadline. Every summer we traveled. Hong Kong. Vietnam. Beijing, with an assignment from Travel and Leisure. He made me walk ahead of him, so when he saw a shot he could catch it without alarming the grandmother selling little bundles of scallions or the fortune teller asleep in his lean-to.

I love this mysterious photo, though no one has ever bought it. Photo: Steven Richter

I was often amazed by what he saw that I didn’t: the image of the Ponte Vecchio reflected in the brass buzzer plate at the entrance to an apartment building. A Paris street through a soaped-up store window. Menace in an owl among the broken dolls of a doll hospital in Rome. My friend Harley Baldwin gave him a show in Caribou Alley and introduced him to the gallery owner Portia Harcus from Boston, who showed his photographs in one of Harley’s storefronts. He began to sell his work.

Steven waited for someone to walk by before he took this photo in Angkor Wat. Photo: Steven Richter.

When there was a coup d’etat at the Aspen Art Museum, the staff rebelled and everyone was fired. He arrived in New York with cameras and moved into my place, determined to make a living as a photographer. There was a heady, intense, almost addictive few years when I shared my column at NYM with Hal Rubenstein, and worked three months on, three off. We took off for Southeast Asia, almost didn’t survive two and a half months in India, discovered the silent streets of Venice in winter, explored Tuscany in summer from an apartment over a restaurant in Pietrasanta, lived in a converted nunnery between St. Jean de Luz and Biarritz, in a friend’s borrowed cottage just below Vence, and settled on Avenue Montaigne for the glorious month of retour in Paris. We would come home from Cambodia and Laos, or Peru, or unimaginable luxury in Morocco, where our friend Robert Berger ran La Mamounia, and Steven would have slideshows for friends and collectors. I’d pour red wine and we’d pass bites.

Steven woke us at 5 am to photograph the Hoi An fish market. Photo: Steven Richter

David Rockwell used many of his Asian photographs at Steven Hanson’s Ruby Foo and other projects. His photographs were slipped into the menus at Barca, a Rockwell-designed Spanish collaboration between Hanson and Eric Ripert.

Look again if you don’t see an image of Mona Lisa on this wall. Photo: Steven Richter

In 2000, he discovered the Iris technique of printing slides on water color paper in collaboration with gifted technicians. The texture of the paper created depth, or as Grace Gleuck notes in a NYTimes review of his DETOURS show at Laumont, “…a snowy day in Venice where the city takes on the quality of a Japanese print.”

“What has become an obsession,” he wrote for an introduction to a proposed book called Street Girls, “is aimlessly wandering, totally immersed in the rush of experience, the endless theatre, the quirkiness of life on the street. That’s when I feel most alive.” The book, “Depictions of Women Around the World,” was not sold before he died.

With photos like this at Blue Fin, Steven added luster and sensuality to Insatiable-Critic.com. Photo: Steven Richter.

Steven never meant to be a food photographer - indeed he fought against the digital revolution until his beloved Kodachrome was no longer available. But he devoted himself to mastering it when we launched the website in 2007. I can’t remember exactly when Steven became a little spacey. Always quiet at dinner, he was even quieter, sometimes eyes glazed over, as if lost in thought.

Something was wrong. Something was different. “It’s just normal aging,” the first neurologist said, apparently not even looking at the MRI. A year later, looking at the same MRI, a neurologist at New York Hospital gave Steven the usual memory workup. The presidents backward, three items to memorize, draw the face of a clock at 3 pm.

As recently as July, Steven would click on this photo. "It’s one of my best,” he’d say.

“I would say it’s aphasia or early dementia,” he finally said. He settled on aphasia, the inability to access words, much to Steven’s relief. The words were so close, on the tip of his brain, but he couldn’t say them. Our time together became a game of charades. He would speak and I would supply the words. Sometimes I would watch him across the table at dinner immersed in conversation with one of our friends, words seemingly flowing. His memory of the past was sharp. But he could not remember who we were seeing for dinner a minute after I told him. It took him longer to focus his camera. And often, he would shoot an image three or four times while our food grew cold.

We stopped in a bar for burgers after a traumatic session with the doctor on January 4.

In August, 2011, an MRI showed a small lesion on his liver. At the end of September, after a simple treatment, he was well enough to join me on a ship where I read from my memoir “Insatiable” in exchange for nine days of luxury afloat. We cruised into Venice with tug boats blasting and moved into a friend’s apartment. What a gift: three weeks of Venice where we’d lived for four winters. Son Nico and fiancee Anne came for a week. The Biennelle was on. We sat for hours watching The Clock. We bought our favorite olive bread from Russo and fruit tart from the revered Franco Colussi on the Lungo de San Barnaba. The melting gnocchi at Frascatteria Toscana were so thrilling, we ordered seconds. On our last evening there, the two of us had his favorite razor clams and ravioli with sea urchin at Alle Testiere.

In Venice last October: two portions of ethereal gnocchi at Fiascheterria Toscane.

A new MRI in November showed the liver lesion was under control but, alas, there was something else. “An inoperable pancreatic mass,” we were told by the legendary surgeon at Memorial Hospital. Chemotherapy stretched over three months, since Steven’s hepatitis C-abused liver had compromised his blood, rarely permitting two treatments in a row. He slept a lot, but got up for our reviewing dinners. He still did all the shopping, braving the Fairway hordes in the morning. Everyday he would put on his iPod shuffle and go for a walk along the river listening to the Beatles. His work table was covered with notes to himself, his email addresses, passwords, friends’ email and telephone numbers. He could not access the words, but could write them down. If I asked for someone’s phone number, he could find it.

“Nico is in a relationship with Anne,” he wrote on one Post-it. He read it aloud every day.

This photo of a gondelieri on his cell was among the last Steven took, October 2011.

I suppose it was bliss of a sort that he didn’t quite understand what was wrong with him. He would ball up his fists in frustration when he was told his platelets were too low for the week’s chemo. But now, I don’t remember exactly when, suddenly, the noise in his head was too much. He could no longer watch television. He couldn’t answer the phone or the door. He couldn’t call me in my office. He could no longer edit his film or spend hours on Facebook.

Energized by Nico’s visit, Steven went to MoMA in May and a movie after.

One day he simply stopped going for his walk. He was afraid to go out alone. The hospital called Visiting Nurses and they gave us an aide three hours a day, five days a week, covered by Medicare. He would walk with his aide, sometimes a mile and a half along the Hudson.

Almost every single day Steven would show everyone photographs of Nico: ”My son.”

His oncologist thought it was time for radiation. The radiologist was worried he would fall off the machine or panic when left alone in the room. “Why not wait till he has pain?” she said. “We can always reconsider then.” We signed up for hospice care. I hired aides to cover additional hours and found someone to stay till 9:30 so I could go out to dinner with friends.

When I left in the morning or went back to the office after giving him lunch, he would stand at the door holding a photograph he’d taken of his son at 5. “I want to show you something,” he would say. The same photo twice a day. “This is my son.”

On his birthday May 17, Nico got him to shave and shower, posting his triumph on Facebook.

Nico had written on a piece of paper that he and Anne were getting married in Central Park on June 25. In the morning, Steven would look at the Times and check the date. “Two weeks till the wedding,” I would say. Or, “Just seven more days. You have to eat this salad so you’ll be strong enough to walk in the park to the wedding.” I laced the chopped romaine with tiny cheddar chunks, tabbouleh, which he hated, for protein, avocado for calories, antioxidant carrots (ridiculous, too late), tomatoes for potassium.

Just as Nico and Anne came down the path to the covered pavilion, the storm broke.

Nico dressed him for the wedding and he had no problem walking to the Ladies Pavillon, posing for photographs, walking to the limo that waited on Central Park West, chatting with Nico’s mother at the dinner we gave for six parents and the newlyweds at ABC Kitchen.

On his good days, we went to movies. Usually he hated them. Sometimes he made me walk out before the end. But he loved “Beasts of the Southern Wild.” The captains at Fiorello always gave us a booth, even when he was rude, expressing his demands, and they made sure his bucatini amatriciana had more pasta than sauce the way he liked it. He loved looking at his photographs on the back wall.

After the ceremony June 25, the sun came out in time for family photographs.

Then came a day he didn’t like any of the food he had loved. His favorite rigatoni amatriciana from Salumeria Rosi that I brought home – he hated it. The Naked Bear cereal he poured for himself every single morning was too sharp. It hurt his mouth. He led his aide to Duane Reade, where he remembered seeing Kaliber non-alcoholic beer, and in the beginning he would drink a bottle. Eventually, he only wanted to open the refrigerator door to count the remaining bottles.

After a night when he stood in the bedroom, refusing to go to bed, till he fell, I thought about putting him in a home with round-the-clock care, so I could get back my life, and I would not have to call a neighbor to help me pick him up. Then, a day later, I found him, the real Steven, still there inside, too aware of where he was. “I want to stay home,” he said. “I want to be with you.” We hugged all the time. He who had never hugged.

“You look beautiful,” he would say, he who had never ever said that before. “I love you. I never want to leave you.” We napped side by side holding hands. In twenty five years together I had never felt so loved. When I came home after dinner, he would insist I come to bed right away, even if it was only 9 o’clock. I slept beside him every night except for the week I had a cold and camped out on the lumpy sofa. “Why are you here?” he wanted to know in the middle of the night.

During the week of July 4th we went to two movies and I took him to see “Newsies” on Broadway. The seat was tight for his swollen knees and he was annoyed that he had to stand up for the latecomers. I was sure he would not want to come back after the intermission. But he did. And he stood up to applaud for the curtain call.

Then he stopped eating and drinking. From grudgingly drinking three Ensures a day, eating two bananas and letting me feed him pasta and salad, he refused everything. He left a note for Nico, “NO BANANS.”

”You know you will die if you don’t drink something. Water, beer, anything,” I said. “Are you trying to kill yourself?”

“Yes,” he said. “I have nothing.” He would walk around holding up his now baggy jeans till he was too frail to stand up without help.

Last weekend Nico flew in from California. Saturday his wife Anne arrived. They threw open the heavy bedroom curtains, closed for months at Steven’s insistence. They got him to drink two tablespoons of orange juice and some water. Nico had music playing on his iPad as Steven slept. He sat there holding his hand. We had agreed to let him go.

On Wednesday, before going out to dinner, I napped beside him, but he did not respond when I took his hand. It felt ominous because he had stopped wearing the baseball cap he’d been sleeping in for weeks. “Stupid hat,” he would say, slapping it, then clapping it back on his head. It lay beside him, faded from his walks, fallen from the pillow.

At 9:15, when I returned, I watched the aide remake the bed. She held up his head on the pillow and I spooned five or six tablespoons of diluted chocolate Ensure into his mouth. He swallowed. I gave him two spoonfuls of water.

At 10:30, the overnight aide went to give him his medication. She called to me. “I think he’s gone,” she said. I thought I could feel a faint pulse. “It’s okay, darling. It’s okay,” I said. I put my hand in front of his mouth. There was no breath. Steven Richter. Seventy-four years old. So determined to live through the months of hospital insult and chemotherapy given and denied, finally defeated by demons in his head.

I could not find the rugged mountain man in the twisted collapsed face on the pillow. I’d agreed to let him go. Now I sat stunned in the living room, reading the notes he wrote to himself, the curling crib sheets on his table, marveling at the mind’s betrayal. Not yet ready to be alone.

Memorial contributions may be made to Citymeals.org