January 19, 1976 |

Vintage Insatiable

Café Des Artistes: If It’s Good Enough For George

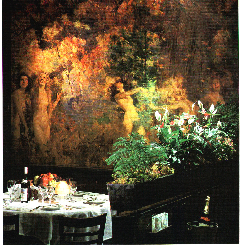

There were rumors. And headlines about a court fight for custody of Howard Chandler Christy’s sweetly innocent nudes on the walls of the Café des Artistes. Then came a letter with the striking asparagus logo of restaurant consultant George Lang. “To abandon or mistreat a child is bad enough,” it began. “But to do the same to 36 old ladies, especially when they are nude, is totally deplorable.”

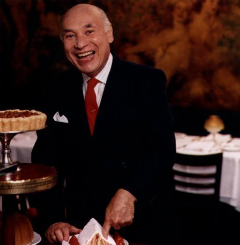

The mistreatment of females in their prime, nude or otherwise, is a sensitive subject hereabouts. So the raised consciousness gave that sentence a second reading in search of sexist insult. And found none. George, self-styled ultimate Hungarian Renaissance man with Byzantine mind, can be calculatedly opaque. It wasn’t clear from his letter if George had bought the Café des Artistes or had merely resurrected it in his role as consultant. “It is really not my place,” his letter said. “I will come as a guest -- just as I hope you will.” That is George Lang -- linguist, littérateur, calligrapher, bibliophile, scholar, showman, violinist, the expert’s expert -- to his friends, clients, competitors, a genius, a dazzling opportunist, P.T. Barnum, something of a charlatan. “It is really not my place...” That is the ever-so-practical Lang, new proprietor of the Café des Artistes...hedging.

|

| |

Haven’t seen George much lately. Word is, George is winging it on four continents, bubbling creative feeding concepts. A thatched-roofed marketplace for the coffee shop of Loews Dominicana in Santo Domingo. An orchid pavilion and freestanding seafood spectacular for the Manila Hotel revamp. Exotic fueling posts in a 400-foot-high Golden Pyramid outside Cairo. All the nutritional diversion in the funicular-wrapped luxury hotel Marcel Breuer is building on Mt. Tochal behind a hill in Tehran. An ethnic bazaar for Manhattan’s now-postponed convention center. Winging it brilliantly, as George himself will tell you. It took him a piddling three days to dream up 29 feeding concepts for the ambitious resort village rising at Porto Carras in Macedonia -- trattorie, pushcarts vending pickled vegetables and souvlaki, gelaterie, crêperies, carry-out delicatessens and wine shops, luxury restaurants and discotheques, samovar service, buffets groaning with the food of Arabia, Normandy, Brittany, Scandinavia, and “Farma Yanni,” a rustic tavern with elderly mamma-papa types serving country fare. “I do everything very fast. Usually in seconds,” George advises. “That Porto Carras memo will become a classic if I say so myself.”

These high-priced jet-stream creative acrobatics represent an amazing recovery. Four years ago Lang’s career was moribund. He’d left an atrophying vice-presidency at Restaurant Associates, as that giant feeding firm’s creeping arteriosclerosis became clear, to buy Luchow’s. The deal fell through. George emerged with his asparagus logo, calling himself a restaurant consultant. It sounded like an interim limbo. But suddenly the world starting consulting George: Marriott, Onassis, Loews, the U.S. government. “There is no competition,” says George. “It’s a business I invented. Nobody does what I do. I’m the only game in town.”

So why bother -- and where will he find the time? -- with an aging little bistro in the western wallows of 67th Street? “Well, if you are a real restaurateur, there is always an itch.” The Langs’ duplex is jut a few doors up the street; George’s office, in a sky lit cellar-garden down below. “I just wanted a good place to eat next to my little Langdom,” says George, “and everyone else is welcome.”

George is fond of quoting Goethe (“Only the good-for-nothings are modest”) before launching an orgy of self-congratulation. The Lang-reclaimed Café, “probably the loveliest surroundings in New York,” is “on its way to becoming an instant tradition, an instant institution,” he wrote me. This time George has scarcely exaggerated. The Café is a joy. George has accomplished a subtle miracle. Some of the nudes are gone, passageways have been banished, windows thrown open to the street, mirrors and masterful lighting installed, a mural of frolicking belles (two in the corner look as if they were surprised naked at the Colony sharing an ermine stole) quite literally slashed in two...a major overhaul, yet all patina is skillfully restored. Enter and retreat into a gentler era, a Viennese operetta. Easy to imagine communion with the ghosts of Valentino, Nazimova, ZaSu Pitts, Al Jolson, Lawrence Tibbett – Hôtel des Artistes tenants once fed by dumbwaiters from the kitchen below - and the Des Artistes Saturday Night Lonely Hearts Club where Peaches met Daddy Browning. The acoustics are painful, but the pain is blurred by warmth and an electricity of cheer. The bar, hidden in a secluded corner, is discretion itself for illicit dalliances or secret drinking. Art Deco-shaded candles cast a rosy cosmetic bloom on every cheek in sight.

“George is off showing Princess Grace how to cut a ribbon in Monte Carlo, dollink,” a Hungarian adventuress assured me that first evening at dinner. George was indeed away launching Loews Monte Carlo with 330 pounds of caviar, oysters flown in from Maine, Bibb lettuce from Kentucky. But his spirit hovered in the unmistakable Georgisms everywhere, some commendable, some sweetly pretentious. And in the teasing lineup of sausages, dill-cured salmon (gravlax, tasting not much like gravlax), cheese and pastry on the long baker’s table cozily crowding the aisle. George’s own calligraphy on the paper pressed onto each butter cup. Splendid pumpernickel and rye, thick cut, in a handled wicker basket. Cutlery turned face down in self-conscious overreach. There are crystal flutes to sip wine from. The waiter brings a sampler of pleasant little wines in metal milk carriers, your choice, $6. The china is calculated to invoke times past. Candles flicker in hurricane chimneys on the windowsill. There are Swiss warming plates, an Italian cheese grater, excellent ice cream (especially silken pumpkin) in banana-split dishes, and very serious tea service using two chunky pots -- one for water, one for tea. And the ultimate Georgism: lascivious Victoriana in the men’s room.

The old man grumping about with a perpetual frown is Charlie Turner, a part owner of the Café for 34 years, kept on by Lang as host, benignly tolerated by the sunny staff, most of them legacies, too. The crew is clumsy and wondrously innocent. When my friend burned her hand on a fiery-hot plate, our Mitteleuropean-operetta waiter went into a stricken tizzy, patting the wounded hand, kissing it to make it better. Amiable. Cheerful. No wonder.

A shabby relic has been reborn. The phone never stops ringing. The house is booked night after night, days in advance. A few weeks ago when George was in New Orleans choreographing four press parties aboard the new Greek cruise ship Daphne -- hanging smilax, inventing an oyster mousse, whipping the French-Swiss-Italian-Greek kitchen into shape (“They have to know fast they are the lion and I am the tamer”) -- his wife, Karen, couldn’t get a table two nights in a row.

Does anyone besides me care that the food isn’t really wonderful? It feels so good in this sensuous room. Critical faculties surrender. I want to return again and again, even knowing as I do after five visits that the food is...merely good, even at times mediocre. “Honest French home cooking,” George promised. At “absurdly low prices.” And there is one $9.50 dinner daily, even including coffee, and pleasant wines in carafe at $2.75 and $3.75. But ordering à la carte push the tariff to $40 for two. And though nothing is inedible, except those gray, tasteless chicken livers, outright triumphs are few: some marvelous desserts baked by the Café’s neighbors, the sublime ice cream, a humble pork-and-veal terrine studded with walnuts, zesty raw-cauliflower salad, a triumph of mozzarella chinks and olives in herb-scented vinaigrette, and tender, flavorful calf’s liver, lightly crumbed and sautéed.

|

| |

The menu is mannered, self-conscious, and slightly confusing. It reveals Lang, never one to shy away from “trying to show my underprivileged fellow restaurateurs how to think,” both defying gastronomic cliché and flirting with it. His gazpacho is studded with bits of shrimp, a spicy, textured deviation. The duckling is tangerined, not à l’oranged, an unremarkable bird. Instead of a classic currant-based Cumberland sauce to serve with terrines of game, he has “invented” a curious emulsion of egg yolk, oil and orange marmalade. At lunch one day it tasted like Gerber baby food pear puree, or possibly banana. But Café regulars are so fond of it the eager waters serve it with anything vaguely porcine, even rillettes. A fine carrot soup needed only salt and pepper, but a classic croûte au pot was an insipid broth with an untoasted slice of bread drowning. Crudités -- homely sticks of carrot, celery, cucumber, radish, cauliflower -- dip into a tart, garlic-scented yoghurt ($2). An order of cochonnailles ($2) brings tiny slices of terrine, excellent sausages, salty smoked ham, and that bitter orange puddle. There are snails sautéed with prosciutto and onions as an entrée ($8.50); bourride, a fish stew with its classic escort, a hotly garlicked aioli ($7.50); moist chicken “in the Maygar manner” ($6.75) in a paprika-tomato sauce with sour cream and a crunch of cabbage. Roast sirloin ($9) is rare and juicy, but the beef itself is mealy and without flavor. There is always a special effort with the vegetables, but the Boulanger potatoes are the kind of home cooking that gives home cooking a bad name. And while the notion of a different pasta every day at only $4.25 to $5 is admirable, the kitchen is not skilled enough to master the necessary timing.

Elisting neighbors to bake meltingly moist chocolate roll and nut-studded Ilona torte is brilliant Langniappe. (“We spread word in the playground we wanted people to bake for us.”) So avoid the artless strudel for baba à l’orange, babka, rich and eccentric mincemeat or raisin pies...all proudly banked by soft whipped cream. George has a weakness for “the flowers of poverty” -- as in pumpernickel cake or neighbor Michael Fry’s buttermilk pie. “Stained-glass artisans were limited to only five colors and they created the rose window of Chartres,” he observes. Alas, he crosses the fragile divide between genius and corn with this strawberry collage -- a trio of small bowls containing strawberries, whipped cream, and pound cake cubes with wooden skewers for dipping. Knowing George’s lust for perfection, I begin to wonder if perhaps his taste is more in his head than in his mouth.

And there is George himself, very spiffy in blazer and turtleneck, fresh from Monte Carlo triumphs, euphoric with the Café’s glorious smash. He has almond cat’s eyes, surprisingly blue, and he looks like a small Walt Disney version of Telly Savalas. He radiates. “You know I did it with the same staff that was here. The chef, twenty years in the kitchen and no one ever spoke to him. ‘Cook me what your mother cooked for you,’ I told him. And the waiters. I taught them how to hold their hands. Some of them are not so good.” He shrugged. “It’s not that kind of place. Now in Monte Carlo, the waiters are perfect. All of them have apple-shaped asses.”

A man with a passion for detail. Perfection. Apple asses. I realized, though I’d know George Lang since his Restaurant Associate days -- known Lang the encyclopedic mind, the collector; Lang the sensualist, the 51-year-old man with a beautiful 30-year-old wife, their swim-in bathtub for two with the refrigerator beside it tucked under the sink, for champagne, orange juice -- I scarcely knew George Lang at all. The minute Lang guessed I might be about to review the Café, he dictated a letter. That’s how George is.

Ask him a question and a few hours later, a messenger arrives with nine pounds of information. Now I treaded a Langian flood: reprints, story ideas, restaurant concepts and memos, press clippings. And a list of friends and colleagues. (“...the list could go one forever. Unfortunately, the most interesting people are in Europe and Asia.”) Among the less interesting: Thomas Hoving. Daniel Boorstin. Harold Schonberg. The John Lindsays. Cellist Janos Starker (“my oldest friend”). Robert Moses. State Senator Roy Goodman. Bill Safire. Gerald Edelman, Nobel Prize winer in medicine (“He’s one of the few people I don’t feel superior to”).

No one, it seems, it at all suprised by Geoge’s spectacular success. There are detractors, some of them too fond of George to criticize “on the record.” “He’s a hustler.” “The ultimate self-promoter, but that isn’t a sin, is it?” “George is the kind of guy who goes into a revolving door behind you and emerges ahead of you.” “He takes too much credit for borrowed ideas.” “He has a kind of eclectic genius, a capacity to gather up information like a vacuum cleaner.” “He is capable of extraordinary generosity and he is capable of psychic murder. He fills all the spaces at the table.” But even the detractors respect his mind, the drive, the professional skill. George delivers.

And listen to his champions: “Nobody comes close to him,” says Loews chairman Robert Tisch. Dieter Straube, who worked with Lang at Loews and who now consults with him for Realty Hotels, Inc. (Hotels Roosevelt, Commodore, and Biltmore): “He’s the best in the business. You give him a problem and within a day and a night, he sits down and starts creating. Should it be a greenhouse? A snake pit? A New Orleans restaurant? He says ‘Now, Dieter, I have the most fantastic idea I’ve ever had. We’re going to make this restaurant...an apothecary. The food will be in apothecary jars. There’ll be an apothecary scale, and the dining room crew will be dressed like doctors and nurses,’ and if he sees you don’t agree, he will switch -- ‘Dieter, this new idea is the greatest...’”

“He is insatiable in every way,” friends say. “He adores his children.” Is fiercely loyal to his friends. For Times musuc critic Schonberg, he once researched and served a Christmas dinner that might have been eaten by Bach, with a Madeira old enough that Bach might have drunk it. His dinners, Schonberg says, “are what the Borgias would do without the poison.”

“He isn’t competing with other people,” Janos Starker observes. “He is always competing with himself to be better than he was. He does too many things too well. People don’t know what to make of that.” Once Starker was with George in a restaurant where a gypsy fiddler played. “The fiddler was awful. George couldn’t bear it. George hadn’t played the violin in five years, but he walked up to the gypsy, took the violin and played it. Better.”

Lang can do four hours on the history of paprika. Those are his essays you’ll read on “Restaurants” and “Gastronomy” in the Encyclopedia Britannica. He is stalled midway in a spectacular book on the art of table-setting and is hoping to do a definitive text on how to open a restaurant. He quit the Bicentennial Commission Festival U.S.A. chairmanship when politics and cronyism and ethnic chauvinism sabotaged all his hopes, and he’s redesigning the fast-food service at the Statue of Liberty...mostly for sentimental reasons. “I’ve never encountered anyone who makes more efficient use of time,” design director Milton Glaser says.

It’s a total recall. “I have a photographic memory,” says George. “I remember what I want to remember. I forget the rest. I wear a polite and interesting face, but I’m not listening...I’m thinking ahead.” A librarian comes in three days a week to catalog his extensive library. He has a staff of eleven -- graphic artists, interior designers, a kitchen planner. On the road he exhausts all companions. (“I go twenty hours a day”). He never stops tasting.

Wherever he goes, George’s khaki travel kit goes too. Inside are currencies of a dozen countries so he needn’t waste precious time changing money; his foreign address book (with a Xerox in his office) listing factories, friends, rare-book stores; a measuring tape in meters and inches; matte knife, magnifying glass, international architectural scale, mini-switchblade (fabric cuttings, fruit cuttings); an eyeshade; a collection of pens in different colors (“In two seconds I can do a design, an invitation, a menu”)’ and his special utensil, a fork and knife in one so he can write with his right hand while he eats with his left. He is never without his Saulnier Répertoire de la Cuisine or a leather case of cooking knives (“A knife is an extension of my hand”). And his notebook. He has filled thousands of notebooks. “Every day I get 100 ideas that are do-able. I’m incredibly fast. My senses, my brain, my stomach, my juices. Ideas flow from me.”

We are in his subterranean office below the Lang apartment with its sunny two-story “greenhouse” extending behind the building. Here are notes to himself: “Pride is postponed prejudice.” And “The first amateur chef was Jacob. The first gastronome was Esau.” “This is a cheese tray like a wheelbarrow,” he says of a small sketch. “Here is soup stand from La Coupole. You can say it’s a gimmick. A lace panty has nothing to do with f------. It’s magic packaging to raise you expectations of what will come. Here is a seafood restaurant. This is a multimillion-dollar idea just on this page. Each line is a whole book of what will be. This is enough for the architects and kitchen planners to get started.”

“Tell me wonderful George stories,” I ask his friends. One of them hesitated. “You don’t have to ask me,” he said. “George will tell you everything.” Those who are fondest of George note that he can be boorish. “He needs to impress. He needs an enormous sense of approval. I find that a charming, childish quality,” says pianist Jacob Lateiner. Another thoughtful friend believes: “His whole career centers around self-justification...proving that he deserves to be alive.” George’s father wanted him to be a lawyer. George wanted to play the violin. To earn money for the conservatory, he worked as a dishwasher. In World War II George escaped from a labor camp disguised as a German soldier only to be arrested by the Russians. He was cleared. He lived. Many did not. He came to America as a violinist. Between jobs he worked for caterers. In three months at the Plasa he worked his way to top saucier, then went to the Waldorf banquet department under Claude Phillipe.

He does not speak of the past. His second wife, Karen, had never heard the whole story till George’s son, Brian, sixteen, asked as a birthday present to hear it all. To me he made a fleeting reference to the work camp, and when I asked him about it he said, “What work camp? That was a private boys’ school. The punishment was very severe, so I invented chain-mail underwear to make it less painful.” An extraordinary fantasy invented, seemingly, at the moment.

“There is an exile sociology,” says Karen Lang, a vice-president of development and planning for Business Week, dimpled porcelain camouflaging a steel core of self-possession and competence. “Perhaps the reason George is so inventive is that he had no models. He came here not speaking English. He didn’t understand the rules so he made up his own. He improvised his own solutions. No one is indifferent to George,” says Karen. “They like him or they don’t. And he is never boring. He is a total original. George is my secret garden. Tomorrow is my birthday, and when I wake up, there will be George standing on the bed, naked, playing Happy Birthday on his violin. He’s flamboyantly thoughtful. He’s also thoughtful in quiet ways, and that’s where it counts.”

One night I came to the Café late, not to judge (I left my professional mouth at home) but just because I find the room romantic. There was George, very elegant, insisting we try eggs chimay -- stuffed with mushroom duxelles and creamy mornay. I asked for some cauliflower salad. There was none on the table. Minutes later, impeccable in his narrow cinched Italian twill, he returned from the kitchen with three different salads. cabbage all over his hands. “I was teaching the cooks how to chop,” he reported. Ebullient. “A violinist’s chopping hand is something to see,” he assures me.

Next day I apologized for my friend’s wrinkled dungarees. “But we want people in black tie next to people in blue jeans,” said George. “A very attractive man. We should hire people like that to come here.” Next time we spoke he was at the Café, his mouth full. “I’m chewing,” he said, “we’re tasting.” Knowing George now and his flair for drama, I know the chew was an artful calculation.

Last time we talked: “My Christmas present to you is not to send you all the new material, the articles, the clippings that came in this week,” he said. “I won’t even tell you about my new project for New York.”

“Please, George,” I asked.

Graciously then: “It will be a restaurant of opposites,” he said. “Tongue-in-cheek, amusing, sophisticated, but not decadent. I signed the contract last night, can’t say who it is...he will remain behind the scenes. But he loves malachite, so it will be real or painted malachite. Everything opposites -- in the men’s room, for example, an industrial steel pissoir beside an artistic but obscene painting by Pascin of two lesbians making love. Pizza with caviar. The name will be La Folie. I might put it in the townhouse with a coed sauna on one floor to give pleasure to more than one sense. But I didn’t even start thinking about it yet.”

1 West 67th Street. Now Closed.