January 1, 2006 |

Travel Feature

Insatiable in New Delhi with Suvir Saran

|

|

|

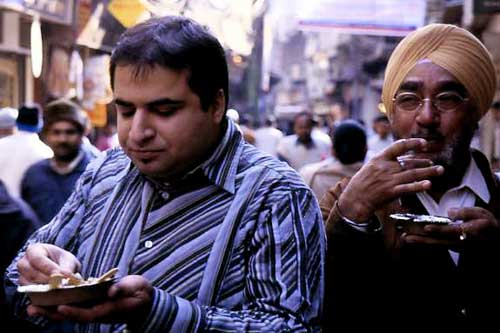

Suvir and his friend, Kaka Singh, sample snacks. Photo: Steven Richter

|

|

The haunting smells of something cooking are everywhere in Chandri Chowk, the main street of old Delhi's sprawling bazaar.They make a confusion of scents calling out to foodie travelers like me from snack food stands, closet-sized food stalls, and rudimentary restaurants tucked into the spice market, between pocket-size jewlery shops, and along streets famous for their wedding saris and savory pancake-like parathas. So I was thrilled to learn that my friend, the engaging cookbook writer and Indian restaurant genie, Suvir Saran, was on his way home to visit his family and to check on Veda, his newly launched black and crystal jewelbox of a restaurant in Delhi's Connaught Circle, a favorite now for affluent locals as well as tourists. Loving Suvir's riffs on Indian street food on the tasting menu at Devi in New York, echoed here in New Delhi, I would entrust the fate of my gourmand hungers in India this past winter to Suvir and explore the source of his inspiration. Then a pair of killer bombs went off in two Delhi markets. Should we cancel? Suvir dismissed our panic. Yes, India has its occasional convulsions of sectarian violence. "But what is more amazing," said Suvir, "is how closely all our many religions live together. I'll take you to my favorite eating streets and you'll see."

|

|

| Photo: Steven Richter |

So here we are weeks later, entering the ancient walled city of old Delhi where the Jamma Masjid, once the largest mosque in the world, looks down on the market frenzy of Chandni Chowk. Muslims live in all these streets, and there is a famous Jain enclave, but by day Hindus shop and come for our favorite treats, says Suvir. After dark Muslims come out to eat in the night market, and we will too. Anyone want a pink pill? I ask, expounding my own faith that Pepto Bismal works prophylactively.

Then off we trudge - Suvir and I, photographer and mates - through the narrow winding alleys, dodging motorcycles, pedicabs, crowded three wheeler taxis, and skinny porters in flip flops, trundling loads so heavy they're out of control, and it's up to us to get out of the way. Suvir's long time Sikh friend, Mahijit Singh (known to his friend as Kaka), dapper in elegantly twisted turban and tweed jacket, joins us to help Suvir trace peddlers remembered from his childhood. We are looking for the Daulat ki Chaat man. Wait till you taste the sweet milk foam, Suvir promises. It's whipped with his bare hands, preferably by moonlight, or so legend says. For Suvir, Hindu and a vegetarian with a passion for sweets, this rich-as-Croesus froth is the perfect breakfast. "This man is the son of the man I knew," says Suvir, as he dips a wooden spoon into a portion of the delicate ooze topped with crystals of sugar, saffron-tinged milk icing, bits of pistachio, and fluttering silver leaf. His father won't tell him the recipe 'til he proves himself. He waits for our murmurs of approval. It's the inspiration of Ferran Adria, he jokes.

We speed walk after our gurus in the corner of Chandni Chowk where jewelers rub up against spice merchants, tasting crunchy chaats, including one favored by Jains and Hindus, too. More than mere chaat, it's a token of Delhi's diversity: grains mixed with broken crisps, and chunks of potato, topped with tamarind and yogurt, similar to those that open Devi's elegant tasting in New York and at the Delhi outpost, Veda. (and in the recipe here for sprouted mung bean chaat with a spicy green chutney). But on the street, the mix is piled into dishes made from banana leaves. Gandhi's dream, says Survir. Reuseable and biodegradable.

Our quest for the master nagori peddler seems futile. So many of these snack sellers have disappeared to become party caterers, Kaka tells Suvir. But a series of bystanders urge us on, waving the way, and there he is with his crunchy bite size balloons of semolina bread, crisper than the inflated poori we know, here served with a savory potato curry noted for its use of asafetida. It's a resin from a fennel-like plant used by strict Hindus and Jains who do not eat onion or garlic for many reasons, including that they are considered aphrodiasical. Suvir explains. He and Kaka walk ahead through the market, spying favorite stands, dispensing aging rupees. "Everything's so cheap," says Suvir, pressing one little leaf saucer after another into our hands: tiny pickles, lentil cakes, nagori filled with halwa (a semolina pudding believers offer to the temple Gods).

At the legendary shop, Ashok Chat Bhandar, we dig into kachori, a dish favored by the nomads of Rajasthan, bites of dough studded with spiced lentils cooked 'til dry so the wanderers could travel with it. Our sample is soaked in yogurt, tamarind, and mint chutneys, with extra spices tossed on top. Then Suvir passes out Dahi Vada, crispy bean dumplings in a yogurt sauce and we fall for that, too.

The streets around Chandri Chowk are such a maze that we haven't a clue where we are most of the time, but Fahim, a Muslim friend of Kaka and Suvir who lives nearby, has found us by cell phone. Will we join him at the saffron dealer's? At the top of a flight of stairs a twist and turn away, we slip off our shoes to sit on the floor. Quickly seduced by the intense scent and apparent quality of this saffron, all of us are buying small packets, 100 grams for just $6. Fahim, is he embarrassed? I can't decide - has come for Shilajit, a resin found in stones from Afghanistan. Supposed to be nature's own Viagra, says Suvir.

|

| Riding in a pedicab through market crowds. Photo: Steven Richter |

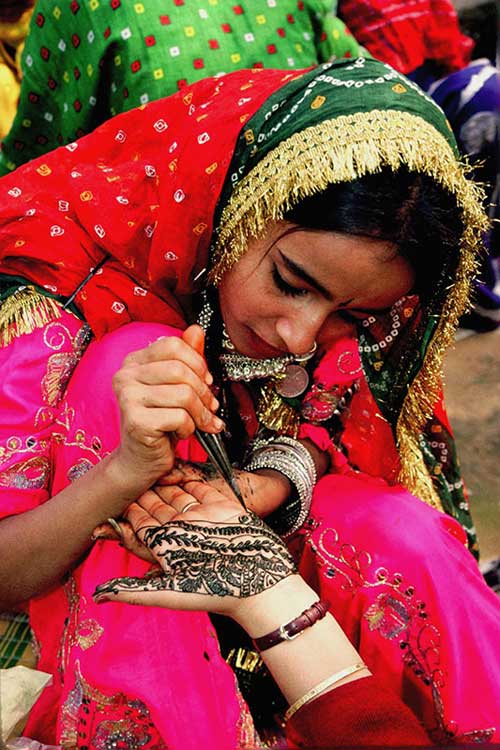

Suddenly we are in Kinari Bazaar, a wedding street, and then a turn takes us past windows with panels of exquisite beaded slik, brocades, and gold-edged chiffon. Everywhere, Hindu women are shopping, sprawling on the floor of sari shops, or crowded close to try on bangles.The occasional Muslim woman passes, all in black. I wonder how the world looks to her through the midnight silk that covers her face. For us, what counts right now is that we've reached the crossroads of the paratha world. Gauging the crowd and the turnover at a crowded little luncheonette, the celebrated Pandit Kanhaiya Lal Durga Prasad, Kaka urges us to grab an empty bench. Soon, slim boy-waiters, slithering through nearly non-existent aisles, are bringing us a marathon of savory flat pancakes in a Baskin Robbins rainbow of flavors: lemon, fenugreek, green chile, cauliflower, lentil, green pea. But it's the tiny dish of fiery pickled radish, turnip, and carrot that excites Suvir. This is what Indians eat to levitate, he muses.

|

| Kaka selects sweets for Suvir’s family and his own. Photo: Steven Richter |

After an outrageous orgy of sweets, including pistachio milk fudge, funnel cakes at the famous Jalebi shop, and lassi (a yogurt smoothie, as Suvir describes it), we have bought giant boxes of sweet pastries for Suvir's family, sampled one of each and are home with less than an hour to shower the crumbs from our hair and grab a nap before dinner.

That night we return to a small courtyard close to the mosque, Jama Masjid, a short walk along Kebab Sellers Lane. Home of the venerable Karim, famed for 90 years of Mughlai cooking luscious minced lamb on skewers, meaty goat curry, and whole roasted legs of mutton from the Tandoori (inspiration for the marinated lamb chops of astonishing tenderness at Devi and Veda, recipe here). The waiter scurries by, bringing voluptuous bread still hot from the oven, returning again and again, confiscating what's cooled. Suvir has said this is one of his favorite restaurants in the world. But it must be the carnivorean joy around him that he treasures, since he only eats the dal, some slivers of red onion, spinach with potatoes, and the yogurt raita (see recipe for a favorite raita that follows). He busies himself rolling our small savory minced meat kebabs dabbed with peppery chutney into neat strips torn from handkerchief-like roti. But when little terra cotta dishes of smooth rice custard scented with rose water and pine essence arrive, he is in heaven again.

"No one makes firni like Karim," he says. Except for the devoutly vegetarian Suvir, all of us are achingly full, but the night is young and Suvir's Delhi entourage doesn't want us to miss the poultry market, Ghazipur, just a short walk away. Here, everyone is cooking chicken side by side in matching iron pans. How do we chose? I think it's the neon sign I fall for: Sahara Chicken Palace. We are the only customers and Nawab Ahmed swirls cubes of cottage cheese-like paneer in a near-irredescent orange marinade with his fingers. Soon, his hand is orange half-way to the elbow. A boy is dispatched for napkins and chairs for the VIPs. The kid returns with pink paper napkins and arranges them in a glass like a rose. He swipes the table with a filthy cloth, wipes some of the sticky stuff from a few plastic chairs. Is it too late for a quick pink pill? I offer them all around. Having survived our high-risk day, we're all over-confident. No one is taking.

The cheese cooks quickly. Suvir loves it. Now the cook skewers chunks of chicken swathed in his shiny mix, infused with garlic, ginger paste, mango powder, and yogurt, and roasts them over the coals with much brushing of butter. A whole line of people have gathered to watch us eat. Ah. It's a bird to swoon over - an edge of char, the tapestry of flavors, an unctuous ooze of butter, the first chicken I've tasted in India that is not dried and overcooked. Suvir, spying the buttery juices, watching the luscious bird disappearing, decides he must taste it, too. That's all he needs to recreate the distinct richness minus the garish food coloring in the grilled chicken thigh recipe that follows.

It is revealing to see yet another Suvir at home. Surrounded by doting Mom and Aunties, as close family friends are always called, we marvel at Mrs. Saran's highly refined transformation of dumplings brought home from the market on a lace-draped table laden with platters. Alongside is Suvir's own special invention from childhood days, when he learned about food by watching his grandmothers cook- the splendid crunch of fried okra salad we love at Devi and Veda. When after a parade of desserts, some of us can barely move, Suvir responds to the family's teasing." Did you know Suvir wanted to be a professional singer?" his brother asks. Sing, cries an Auntie. And suddenly, he breaks into a lilting chant in Hindi that sounds like something between a hymn and a love song, his voice haunting and dramatic. I am thinking, children who are very loved often grow up to be loveable. The sweet charm of Suvir and the strong drive for the spotlight has clearly always been there.

Article appeared in Food & Wine June, 2006