March 15, 2016 |

Short Order

Sushi in a Closet, Imagining an American Bar in Vienna

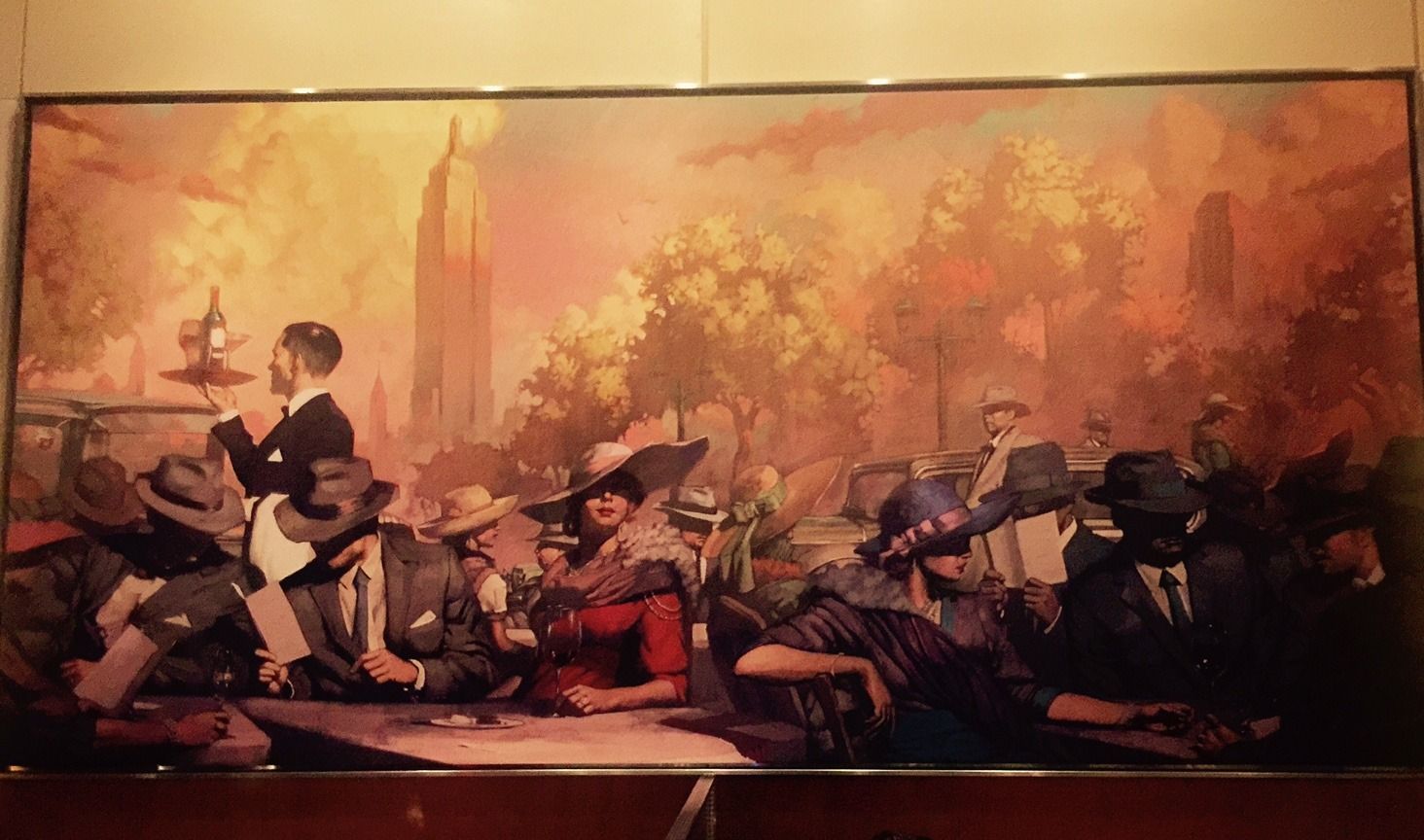

Architect Bloch found inspiration for this custom-order work at State Grill in a French painting.

Masa’s arrival with a shocking $350 omakase at the Time Warner building was the talk of the town in 2004 when its architect, Richard Bloch, invited me to what I thought was a pre-opening friends and family performance. (Click here to read “Will $500 Buy Piscatory Nirvana?”)

The two of us were alone at the 26-foot imported hinoki-wood sushi counter – inhaling the scent of cedar with each sip of icy sake from wooden cups. It was a moment of high drama as Masayoshi Takayama positioned his cutting board and began slashing away. I was so mesmerized I scarcely noticed the later arrivals.

Since then, over the years, I occasionally get calls from Bloch, eager to share a meal. At first, I didn’t have a clue why he was so taken with the small mahogany benches at Yopperai, a closet-size izakaya half a flight up on Rivington. “You can store your purse and your jacket down here,” he said, removing a traditional Japanese wooden key in the door latch of my perch. And then I got it. Of course, it was his design. “I thought I mentioned that,” he said, laughing. The budget was ridiculous, the space, impossible, he told me. He admired the refrigerator hanging from the ceiling at his instigation. “I have a lot of fun when the budget is tight.”

He offered to help if I couldn’t get into the very popular Neta, where everything in a quiet sushi bar that would normally be out back was up front because there was no “out back.” I was unsettled by the chaos. I figured it was one of his budget adventures. I decided to try to accept that a serious sushi destination needn’t be a temple of silence. So, when the Neta team, Nick Kim and Jimmy Lau, went off to open Shuko, I was not surprised to run into Richard, grinning with a certain pride, and another slab of tree forming a counter that required sanding every day. “Did I miss the press release?” I wondered. I got him to point out the design elements I might have overlooked.

Bloch’s design for Nick Kim and Jimmy Lau at Shuko leaves room for a drink bar behind the counter.

Last week at dinner, he was very mellow as he explained that he plans to move to Japan in a few years. It seems he fell in love with Japan and with Hiroko, who became his wife 40 years ago, while he was working in Tokyo on U.S. government projects. Hiroko runs the office. For years, he’s flown back and forth on work. The office stays in New York. He will commute. I prompted him to talk about what brought him to architecture.

“I knew I wanted to be an architect at eight or nine,” he said. “My mother was kind of left wing and artsy. She took me to museums and galleries. First, I thought I wanted to be a sculptor. In shop class, I realized I wanted to be a carpenter. But then one of my teachers said, “No you don’t want to be a carpenter, you want to be an architect.” He got a book to see what that meant.

After the years in college and then at Pratt getting an architectural degree, he spent a year in Turkey on a Fulbright. Then, he took three months to travel around, “just looking at cities and buildings.” In Rome, there were 121 buildings he needed to see in six days. “I didn’t miss a single one. “

Home again, he took the dreaded architecture-licensing exam and passed. “I figured that meant I ought to get a job.” A friend sent him to see Phil George. At that point, George, an interior designer, was the go-to guy for Restaurant Associates. That’s how Bloch found himself working on restaurant design. “I learned everything from Phil.”

“I thought, this stuff is really exciting,” he recalled. “I found I liked the challenge of restaurants. Restaurants are very complex, second only to airports and hospitals. You need to know everything. Engineering, plumbing. Lighting. You need to know about engineering because you don’t want to be dominated by the engineer. Wiring, pipes, ducts, ceiling heights -- you have to know all those things.”

“I never aspired to be a Frank Geary and do a Frank Geary building or even a Frank Lloyd Wright, where everything is in their style. I don’t care about doing a museum. I’m not interested in a legacy. I wasn’t going to be a minimalist or a traditionalist.

He studied the Art Deco motif of the Empire State Building for his design of State Grill & Bar.

He stayed with George seven years, then went off on his own. “I don’t do a Richard Bloch restaurant,” he told me. “Each restaurant has its own design style. I’m a funny guy, I guess. I’m different than many architects. I don’t photograph the work. I don’t hang drawings in my office. I don’t send out press releases. I don’t have a publicist. When I’m working, the most recent designs are my favorites.”

He urged me to check out Patina Restaurant Group’s State Grill & Bar on the ground floor of the Empire State Building, one of his most recent projects. I’d refused to write about it when it first opened because construction hid the entrance on 33rd Street.

The lamp is by the Austrian modernist Adolph Loos. Bloch ordered it from the original factory.

“It’s finally finished now,” he said. And the sidewalk construction wall is gone, he assured me. “It was a tough challenge because so many things couldn’t be moved, the pipes, the ducts, the wiring. There was one overarching requirement: Patina chief Nick Valenti and the building owners wanted a place that looked modern and art deco, too. He started by studying the building design. “I knew it should be lightly art deco, restrained like the building itself. It wouldn’t be flamboyant art deco like the Chrysler Building."

The small sushi bar at the Sony Club was built with precious materials in a closet-like space.

He’s right. The State Grill and Bar is a gorgeous space with gleaming chrome accents, brilliant color, abstract images of the Empire State Tower etched on the glass wall that divides the bar from the dining room, and a large painting on the wall that looks very Don Draper. Bloch had it painted to order. And the very heavy metal 1908 table lamp at the end of the bar is homage, a design by Adolph Loos, an Austrian-Czech pioneer of modernist architecture. Bloch was so enamored with the $2500 lamp – still manufactured by the original Austrian workshop, that he ordered one for himself.

Not long after this conversation, my friends and I settle into a booth where I find myself marveling at the audacity of covering a restaurant floor with a thick wool carpet. What an extravagance! The carpet is a shimmering grey, almost luminescent.

“But what if someone drops a some beet juice?” I ask Bloch at our next dinner.

“It’s wool,” he assures me. “Wool is easy to clean. It’s nylon you can’t clean.”

If forced to run a restaurant, he might choose Benu, the design he did for Corey Lee in San Francisco.

Does he have a favorite design? He grins. “I am very fond of the sushi bar at the Sony Club. It’s just a five-seat sushi bar I did with Quilted Giraffe chef Barry Wine for Sony. We did it in an awful little closet off the main dining room. It took three months, and there was no budget. The founder of Sony wanted it for his sushi lunches. The wall panes are custom made Japanese lacquer. We ordered the cotton woven for us from India. We used Barry’s Quilted Giraffe sushi bar with its hollow along the far edge so that water from the fountain runs through it. Charles Gwathmey’s office designed everything else. But I did the sushi bar. I ate there once. That was exciting for me.”

This is the tranquil courtyard entrance that leads to Benu.

I asked if he would send the photos that you see here. “If I lost my mind and chose to open a restaurant, Benu, the restaurant I did for Cory Lee in San Francisco would be the place,” he wrote. In 2014, Benu earned its third Michelin star. I’ve only seen the photos here, but I have to think the serenity of that entrance and the open kitchen surely deserves some credit.