January 1, 2002 |

Travel Feature

Barcelona Dine-A-Thon

|

|

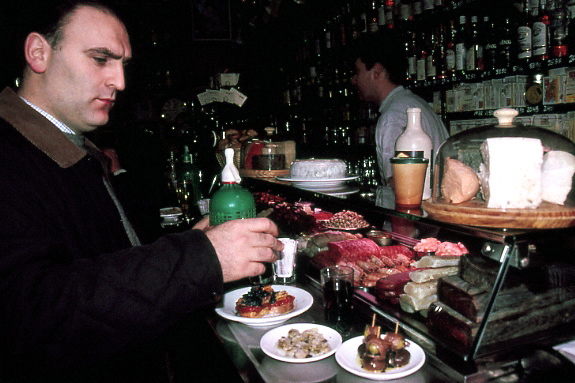

Jose Andres savors canned treats at Quimet y Quimet. Photo: Steven Richter

|

Jose Ramon Andres has two passions. Well, actually, the Barcelona-raised chef of Jaleo in Washington D.C. bristles with irrepressible enthusiasms. So let's say, two grand passions: America and Cataluyna (not necessarily in that order.) A mutual friend asks him to email me a list of his Barcelona favorites for my winter retreat there. “I wish I could go along and show her My Barcelona.” The email says.

Ten days later, it's a fact. He arrives. January, 2002. I am rubbing cheeks with a burly stranger in a green cardigan and baggy jeans at Suquet de l'Almirall, a waterside power-lunch spot in sunny Barceloneta. (It's Catalonian etiquette to rub cheeks and kiss the air on introduction.) I've never met Jose before. I don't know Jaleo, where he feeds 1000 mouths a day. I never set foot in the more ambitious Café Atlantico, where he ignited early buzz with tricks learned at the elbow of Ferran Adria at El Bulli.

Just off the plane, Jose Ramon Andres is raring to go, energized by his mission. I am going to love Barcelona. I will taste the best tapas, visit the best countryside masters, be tutored in cod and sea cucumbers and canned tuna and the art of eating calzot - a leek-like tuber that hits its prime in February. The tomato bread arrives. His anthem begins: “The Catalans were the first cowboys. Our coca (any flattened crisp or bread) is really the first pizza,” he observes. “It was poor people's food. You are sanding the tomato with the rough grain of the toast. Now in the wealthiest areas of Catalunya, a meal cannot begin without pan-tomate.

Andres' orientation riff punctuates lunch, a daunting parade of tapas (in sharing portions) from the kitchen of his onetime schoolmate, chef Quim Marques: First the obligatory foie gras with onion marmalade on a slice of potato and more humbly, cod fritters. Then wave after wave of immaculate sea creatures, not more than half an hour out of the water, he judges. Tiny clams tossed with bits of ham and a hint of Pernod. Pulpitos (teeny octopus) “just touched by the fire,” Andres comments approvingly, with caramelized onion and crystals of salt. “In Spain, we catch seafood like no one else.” Baked scallops. Cigales (spider shrimp from the sea) interwoven with slices of truffle on skewers. Baby cuttlefish - just arrived - with sun dried tomato. Huge heads-on shrimp. He inhales deeply, "That smell is how I know I'm home." Rice with cuttlefish and cepes. Exquisitely cooked monkfish. Two very different sheep cheeses. It's the house's usual tapas tasting, times two, with some high-priced items thrown in for the return of Barcelona's conquering hero.

He swivels his rented car free from where he's hastily jammed it in. “I know it looks like I don't know where I am,” he says, dodging the wrong-way into a one-way street. “My wife is always saying I am a guy who can get lost in a glass of water.” He brakes at our corner. “You are going to be amazed, “ he promises, fixing me with big blue eyes. It's never been a better time to eat in Barcelona, not since Arzac met Paul Bocuse in Madrid in l968, and the revolution of high end cooking began. Now Ferran Adria has put Catalunya on the map. He advises us to nap for the next few days' marathon.

|

|

la Boqueria's fruit mongers dress up to greet the day. Photo: Steven Richter

|

Next morning we find him at Barcelona's vibrant La Boqueria market, off the Ramblas. Young, with thinning hair slicked back and rosy-checked (after a late-night wine tasting with old cronies), he pays homage to fried sardines on tomato bread and a plate of gambas with beans at the legendary Bar Pinotxo. (A must if only for its luscious custard-filled donuts and café con leché.) He cuts a swath through the market, directing our attention to the couturier cod stall (“Cod is nothing, a boring fish, Add salt and it comes alive”), dismissing crustacean also-rans, singling out the royalty of fishmongers, introducing us to Llorenc Petras, lord of wild mushrooms. The two of them stand belly to belly, enthusing over boxes of earthy tubers. As we exit through an alley, Jose spies the venerable chocolate and pastry shop, Escriba, and disappears. Though the window, we watch him munching a donut as he fills a sack with breakfast sweets for us to sample.

He checks his watch. It's almost tapas time. “Quimet y Quimet (another youthful old pal) has the best premium products in cans,” he says, as we press through the crush spilling onto the sidewalk from a small Bar-Bodega (its walls paved with spirits, domestic and imported). Local cognoscenti are already balancing noon-hour snacks at narrow standup counters. “Can?” I sneer. “Cans are really important in Spain,” says Jose. “You can't get a fried clam on top of Mt. Everest.” He sips a Cava and suggests I try red vermouth and soda. Our tasting plate brims over with aristocratic tuna, a sturdy sardine with hake eggs (dried and pressed with almonds) on toast, preserved peppers, an haut anchovy and pickled onion speared on a toothpick with olive and anchovy. “I love eating with a toothpick,” says Jose. “To me the toothpick is the next best tool for eating after the chop stick.”

Andres has given up the stressful parking sport and garaged the car. So we taxi to the legendary Isidre, another power lunch canteen. Alas, it's only 1:45 and waiters are still vacuuming. So we cool out at a nearby sidewalk café where he pulls out a packet of Listerine's green oral care strips and slaps one on his tongue. “You must try it.” he urges. “It's the essence of mint. You could dip this in chocolate and put it on your tongue - you'd have the perfect chocolate mint.”

Andres is just 31 but there are already scattered threads of gray in his sideburns and seeing pals from culinary school in their own places sets him brooding. Besieged by the devils of instant success, he left Atlantico overnight to run the fiercely successful Jaleo for demanding partners. “The expectations were so high, maybe I'm shooting in my foot my dream. I want to have my own place, sixty seats, my way. For now, I do the food of my mother.” But he has agreed to open a Middle Eastern canteen for his partners and the dream seems even farther way.

“This is the Sirio Maccione of Barcelona,” says Jose, introducing us to Isidre Girones, the natty doyen of Barcelona restaurateurs - one of the very few who still comb La Boqueria mornings for the freshest arrivals. We get the Prodigal-Son-Returns tasting, creamy clots of egg in its shell as an opening gambit, then deep-fried cod-and-parsley fritters followed by local chanterelles, with bacon and a poached egg on top. I've already eaten more eggs in two days than in a year of my normal life, I complain to Jose. “Do you think we could have some vegetables?”

“The Spanish do love eggs,” he admits. “Eggs, honey, sugar, and almonds. Give me these four products and I can give you 1000 recipes.” He signals Girones. Now come fried aspargus and then big cubes of artichoke heart sauteed with bacon. “We do the best frying in Spain,” says Jose. “Everybody talks about tempura, but we are the experts on frying.” Just as we tuck into our loamy, wild chanterelles, the mushroom vendor himself arrives for lunch. “How small is the world,” Jose marvels. Now it's foie gras melting in a big artichoke heart followed by lumpy little beans dotted with baby squid. “Puntillitas, deep-fried like popcorn,” he notes. “Classically, these beans would be served with blood sausage." This is the seafood version. It is an impressive homage to the market, we agree, as a froth of bitter chocolate arrives in yet another egg shell. “Simple things need to be just great,” says Andres.

Jose's boosterism never flags. His sole sacrilege all week is the brave confession that he promotes Cava, but prefers French champagne. “I'm 19 years in the States. I feel integrated. I have a double role. I tell my friends here the greatness of what is happening with food in the States. And in America I spread the word about Spain. We have better cows. Better pork. Better beans. I know I sound very chauvinistic. But I have eaten beans in France, Italy, South America. Fabes. This is the bean, huge and buttery, the skin melts away in the cooking. It costs $25 a pound. You know in Asturias (my birthplace), we have the grandfather of cassoulet. It is our regional dish. Chorizo, blood sausage, garlic, beans, four or five hours to cook it. Cassoulet, no?” He grins in triumph.

He has warned us the evening will be a triathelate of eating in trendy El Born (Barcelona's SoHo). Indeed, it is an intense sensory-bombardment, a gorgeous blur of eggs and blood sausage, mysterious foams and sabayons, and exquisite sea food documented on my stained notebook pages. A warmup tapas tasting at the small and cheerful Santa Maria, with its clever do-it-yourself-on-a-shoestring design. Yucca chips, meaty fried won tons, pinky-nail-size clams, and soy caramelized frog's legs. A toss of wheatberries, hazelnuts, and vegetables laced with mimolette cheese calls for an encore.

Around the block at upscale Comerc 24 - a shadowed marvel of Barcelona's flaunted design creativity - Jose signals chef Carme Abellan, his onetime El Bulli teammate, to wow us. And he does. With onion soup poured onto a poached egg on camembert. Calzot (a spring leek like onion) tempura. Inventive sashimi, bruschettas in tangled flavors. A ridiculous do-it-yourself omelette that happens to be delicious. Sardines slashed with premium balsamic and frosted with parmesan dust. And a glass cup of spicy blood sausage parmentier under potato foam. What is this? It looks like scrapings of leftovers. But it's sweet carpaccio of langoustine with tangy rivulets of its own juices, a dazzler.

No wonder we can barely do justice to Epais Sucre, a pastry school cum café just steps away, where dessert tastings are the newest tapas twist. Three full-size desserts with little cookies and candies, bottled water and coffee or tea costs about $19; a five-dessert tasting, $29. We can barely handle two, both too sweet for me.

Miraculously, we are actually hungry again next day on the 45 minute drive north to Sant Pol de Mar for Saturday lunch. “I don't like to difference a chef by gender,” Jose had written in his email, “But Carme Ruscalleda is the best women chef I ever meet...Her cooking is inspiring.”

This is definitely a two-star Michelin aura : The giant table set for three overlooking a wintry garden and the sea. The bustle of smartly uniformed servers, the crisp buttercup linens, the poise of the host Antoni Balam (Carme's husband). Ruscalleda revision of classics are complex, exquisite, even daring (as in calzot sorbet with romesco sauce, wearing a tangle of candied vegetable julienne. ) Too often sweet, I note and Jose chides me: “Spanish like sweet and so do Americans.” But small quibbles are forgotten when the captain pours a powerful onion soup over a poached egg splotched with truffles, beneath a bridge of nutty pastry. There are shrimp elevated to transcendence in a citric fricassee of pristine seafood. And the pleasure never falters through Tordos (a faintly gamey little bird, juicy and rare, with lush potato puree and a quintet of cheese, each with its accessory: a sorbet, a confiture, a gell), leading to Mandarin sorbet and some chocolate decadence. (And it's just a half hour by commuter train from Barcelona's Placa Cataluyna).

Andres wants to show us the Barcelona Taller (atelier) of El Bulli where Ferran Adria (Jose's God and Mentor) and his team spend the winter inventing next spring's menu astonishments. We see slides and scrapbooks, the newest tableware, hypodermic needles to shoot shrimp essence into your mouth. Both Adria brothers, Ferran and his pastry chef Alberto, are away promoting Cataluyna in Tokyo, so Jose invites Ferran's wife and Alberto's girlfriend to join us.

The bar of Estrella de Plato is already jammed with fans who come for tapas, creative and classic. The menu is no help at all, so many strange words, in both Spanish and Catalan. “You just look what's in front like at a sushi bar,” Andres instructs. “Then see what is everyone eating around you. What people do, you do it, too.” He waves his hand, clicks his tongue, hisses. VIP regulars can claim a secluded back-room tables. Needless to say, the chef is on our case. I remember an immaculately fried langoustine, fingers of steak in gorgonzola sauce in shot glasses, baby shrimp simply steamed in their shells. And more and more.

|

|

There is a ritual to eating the first calzots of January. Photo: Steven Richter

|

“Whatever you do, you must go to a calzotada,” a Barcelona-addict friend insists even before I left New York. So I am excited when Andres decides we will spend Sunday in the country at a friends' family Calzotada. We'd already tasted the leek-like calzots, an early spring onion, steamed, in tempura, and in sorbet. I must say a calzot is not a truffle, not close; not even a porcini or a purple-fleshed peach. But because of Andres, it was our privilege to share this warm and loving family's ritual January celebration of the tuber. A dazzling sun warms the air in a hidden garden in the Catalan town of Guissona, where we are welcomed with many grazings of cheeks. Kiss Kiss.We are more than 90: newborns and toddlers in strollers. Kids poking turtles and dragging two-wheelers through the grass. Women gossiping, flirting, and setting the long tables. The men stoking the fire that blackens the huge harvest of calzots. Jose plunges in, grabbing the hot stalks with his bare hands, wrapping them in newspaper to stuff in cartons. Once several hundred singed calzots are packed away to steam themselves tender, the fire is tamed for a load of chorizo, blood sausage, and thick bacon slabs.

A steaming newsprint package resting on a roof tile is set between each twosome. Jose opens ours. It's tricky to strip away the scorched outer leaves without losing the tender shoot within. My guy gets the knack right away and devours 25 or so, dragging the tips through delicious romescu-like sauce. I feign helplessness and get mine manicured for me. Jose thrills the romescu cook by asking for her recipe. It's been a long day for Jose - cooking, flipping, driving, getting lost, charming the multitudes, baking in the sun - he begs off for a night to cook for his family.

Monday is his last full day. Jose Ramon is desperate to fit everything in. We join him at Alberto Adria's chocolate shop, Cacao Sampaka, for breakfast. Jose has ordered a brioche, tropical juices in tall glasses, coffee-con-leché and a fabulous melt of cheese and ham on toast. It's too early for chocolate cake and chocolate ice cream, but who knows when we'll pass this way again…we taste them too. And Jose buys half a dozen boxes of chocolates for gifts. He leads us to Quilez Colmado, a gourmand emporium sincee 1908. “Look at these cans,” Andres cries. In the windows are stacks of foie gras tins, the best tuna, the rarest anchovies; in the far window a haunch of air-cured ham, “the best, the best, the best.” He picks out cheeses, some anchovies, and two bottles of wine to take home. One bottle is shockingly expensive. “I'll put it on this credit card so my wife doesn't notice,” he confides. He hands me a giant wheel of frosted coffee cake from Mallorca “for your breakfast.”

Next he checks out the newest cookbooks at the Libreria Francesca. Nothing he needs. He ducks into the housewares bazaar, Vincon in a landmark building with an inner terrace that looks out onto Gaudi's La Pedrera next door. Checks out tableware. No sale. Now he must meet his sister-in-law who will help him buy new pants. “Because good pants are better in Barcelona,” he says. “And cheaper.”

We are back at Estella de Plato for a farewell dinner. Again? Yes, we should have stayed there Sunday night. It was good. We will taste more. He can't quite believe how badly the pants expedition went. “I try 35 pairs and not one fits. I don't know what happened.” He laughs.

I hate that he's leaving, though I'll definitely enjoy a big salad for lunch and sleeping through breakfast. “You'll come to Jaleo in Washington,” he says. “I'll cook you paella. You'll taste my new chocolate truffle with foie gras inside.” It's obvious I have fallen in love with Jose Ramon. But I can't help myself. “Jose, it sounds ghastly.” He is not daunted. He's confident he's got it right. “You accept chocolate in mole, so why not? I wrap a creamy foie gras around a frozen tamarind cube. Then I coat it in melted chocolate (mostly bitter) and roll that in cinnamon-spiced brioche crumbs and deep fry. You pop it in your mouth and it explodes. You will like it. People are loving them like crazy.”

Two days later, an email comes with a revised list of where we must eat.

***

A version of this story was published in Food Arts, October 2002.