February 19, 2018 |

BITE: My Journal

Remembering Andre Surmain

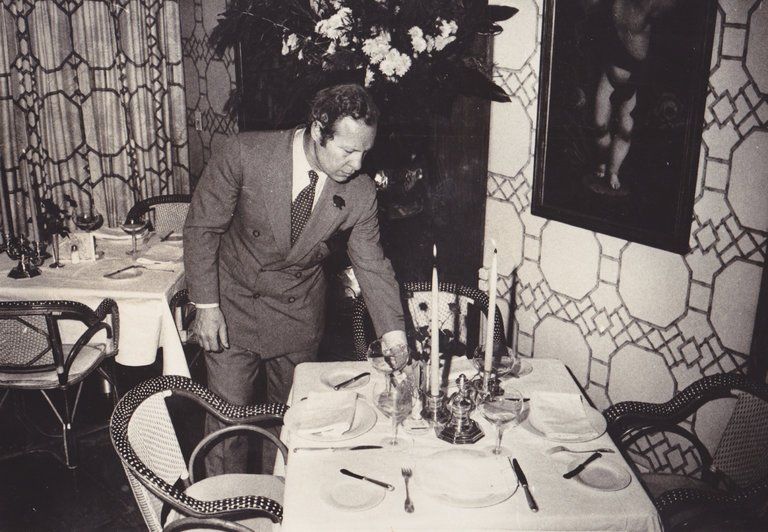

Craig Claiborne was offended by Andre Surmain’s sartorial style in the dawning of Lutéce.

Memories are newly delicious, full of fun, stolen afternoons, secrets. Someone has died that you’ve lost touch with, but knew in your golden days (for me that would be when my thighs were perfect). The Times obituary by Sam Roberts on February 1 took over my day. “Andre Surmain, Who Fed the Elite in Luxe Style at Lutèce, Dies at 97,” was the headline. Did you see it? Click here.

(By the way, Andre would have been deeply offended by inelegance of the word “Luxe.” A deadline writer’s resort.)

Read the Times obit (click on the link) to learn about Surmain the warrior and Surmain the caterer.

Did you grow up as an early foodie too? My friends who lived nearby -- let me call them Alicia and Michael -- in 1961 noticed that the townhouse at 249 East 50th had become a restaurant. They walked in that first week although they didn’t have a reservation and got a table since almost no one was there. They were so impressed by the food that they made a reservation to return the next week.

“Surmain greeted us,” Michael recalls, and said, ‘Yes, Mr. Lippman, your usual table is waiting for you.’ We had never asked for that table, but from that time on we ate at the same table until André Soltner retired.”

***

"Lutèce: Miracle on Fiftieth Street.”

The Times photographer captures the elegance of the dining room.

In 1961 Craig Claiborne had described Lutéce as “impressively elegant” and “conspicuously expensive” but disparaged the food and the sartorial style of its host. Claiborne was offended that Surmain wore tweeds and Hush Puppies and kept pencils in his pocket. Two years before the Times gave Lutèce three stars, I had located its unique pleasures for my readers in “Lutèce: Miracle on Fiftieth Street.”

“France travels so well,” I wrote. “France undiluted thrives at the Restaurant Lutèce…brilliant, eccentric, individual and alive. Alive, and therefore inevitably flawed, Lutèce is the witty and civilized creature of Andre Surmain.

“In the beginning…Henri Soulé, the great god of transplanted gastronomy, created Le Pavillon. His disciples were overzealous in pious imitation. The classic mold was cast. Fine French Food, Manhattan Division, meant red velvet banquettes, crystal sconces, Siberia for the lady from Kalamazoo and a tuxedoed cold shoulder at the door…your host as benevolent despot and Super Servant.

“Not for Andre Surmain. He can rip up a check and eject some hapless peasant as despotically as the next autocrat. But Lutèce is not a dining room. It is Surmain’s home. He is not a super butler. He is your host, a zany country squire with his fat lapels, the bluff blend of pinstripe, tattersall, stripe and Art Deco abstract. It is a highly aristocratic vulgarity, especially those crepe-soled rust suede Hush Puppies…” It suits.

“An abrading Manhattan decade has failed to dim the glow of Gallic soul at 249 East 50th Street. There is France’s tricolor fluttering in the urban choke above the awninged sidewalk of Surmain’s pygmy townhouse. Narrow hall…on the right, a sawed-off bar beneath a wail of temperance: “L’alcoolisme fait de l’homme une brute.” Tiny tables, a homey hodgepodge of memorabilia: a Paris street sign, “Place de Furstenberg,” letters, Lutèce credentials, awards, prizes, diplomas, affiliations. Surmain has more merit badges than a pre-Aquarian Eagle Scout.

A view of the covered garden room by a photographer for the Times.

“Past a tiny slip of kitchen -- ‘the miracle on Fiftieth Street,’ Surmain marvels -- is the sunroom, fresh, lucent, summery even in the drear of winter with its shiny porch wicker, yellow plaid tablecloths, trellis walls, and balloon stemware, the silver set bowl down à la mode Française. Beyond, the garden is ceilinged in plastic that blurs the skyscraper thrust and shields against all inedible missiles. The full defiance of flowering greenery will be back once workmen get the new air conditioning-heating capsule in place…faux summer year-round. Upstairs is more formal...Aubusson tapestry, marble mantels, silver girandoles…a living room with tables set for four.

“The menus are dazzling graphic excursions…at night, in numbered editions, à la carte prices listed on the host’s carte only. Even the tailored $8.50 prix fixe lunch listing courts the jaded palate by brushing the clichés lightly and adding cold pike pâté in pastry with watercress sauce, morels in cream, fleshy cèpes á la bordelaise, chicken or lamb wrapped in a flaky croûte…adventurous plats du jour, always a few fresh flights of fancy on the dessert table.” Click here to read my first review of Lutèce.

***

Au Revoir, Andre Surmain

He was a rogue, flirtatious, irresistible. My favorite memory of Andre was being in bed with him one afternoon, in after-sex languor, when he confided to me that he was really interested in another blonde writer that he saw often. No, I didn’t kick him out of bed. I knew we were just about sex.

I am stunned now, reading the obit, to realize that he lived to marry four times and be 97 long after he ceased to be a character in my life.

“Love is still the best game in town.” I wrote in ‘Au Revoir, Andre Surmain.’ “And a man in love is absolutely beautiful. Andre Surmain loves his life. Antique motor cars, Majorca, sailing, his family…his name, his triumphs, adventure, but not necessarily the incessant detail of running New York’s most consistently pleasing French restaurant -- Lutèce. A few weeks ago Surmain gathered fourteen friends and champions to mark his 52nd birthday -- gentlemen in black tie, women decorously bared and brilliantly painted, all palates keen in great expectation.

“After the tease of champagne and the fresh foie gras in brioche, after lobster à l’américaine and one of the house’s voluptuous inventions -- a pastry package of veal and sweetbreads and brain -- after the ’55 La Tâche and the ’49 Lafite-Rothschild and an exquisite chestnut vacherin in counterpoint with the nectar of d’Yquem, came the non-surprise: Surmain had sold Lutèce to his sorcerer-chef-partner, André Soltner.

“Everyone thinks I’m crazy,” Surmain brooded, but only for a moment. Exit in triumph. The irascible maverick, champion…and lover. Crazy? Or the sanest man in town?” That was January 1973. He was selling the restaurant to Soltner, and moving with his family to Majorca where he would open Fuc e Fum. Click here to read "Au Revoir: Gather His Rosebuds," January 1973.

***

The Latest From France: The Eloquent Dollar

Ultimately, there was another blonde, and he would leave the restaurant in Majorca for his wife to run. He opened Le Relais a Mougins with a new wife. My reviewing rounds ultimately brought me there.

“If Verge is a the crown prince of Mougins, then our own Andre Surmain, the creator of Lutèce, must be the village’s barbarian invader, but what a seductive and talented barbarian he can be.” I wrote. “Since announcing his retirement at 52 and selling Lutèce to his gifted partner-chef, André Soltner, Surmain’s life has been a Mediterranean soap opera. In the latest episode, his beautiful new blond wife has run off with a waiter. In the drang, Surmain’s Relais a Mougins lost one of its two stars. But now, in June, he is sunny again, cheered by having his daughter and her husband in their own little bistro across the way, dashing in his sparkling chef’s whites. In top form he is irresistible – gossipy, candid, and wryly self-mocking, proud and passionate – as he cozens the flock, urging them to try his nouveau pink champagne and his Provençal wines made from a single variety of grape: Cabernet, Gamay, or Chardonnay.

“Of course, we are welcomed, hopelessly indulged, with Andre insisting we try a taste of almost everything. Dinner is delicious, now and then slightly flawed, but the evening crackles with wit and warmth, clearly not ours exclusively, judging by the overhead purrs of other departing clients. Church bells chiming. Handsome green-edged white octagonal china on green tablecloths. Lush flowers. Too soft but good country bread. Fabulous packaging for snails: a splash of melted garlic butter, chive, a buttery crouton, and a dab of crushed tomato.

“Oysters are tucked into individual pufflets of pastry with tomato dice on a bed of spinach, richly sauced. Creamy curried scrambled eggs with sea urchin are served in the eggshell with chutney and toast cut like French fries for dipping. A trio of fish are presented in a cream-enriched fumet with slivers of red pepper, and then foie gras – “the cocaine of France,” quips Surmain – with port jelly and a glass of ort to sip. Tenderest chicken is napped with a creamy velouté of pea. On the side, we get slightly floury noodles tossed with vegetable julienne. And duck breast comes with chive butter, and celestial spinach in an iron marmite.

Le Relais’s chocolate velvet is dense and deeply haunting, stolen from my recipe. Although to be honest, I must admit I borrowed it myself from Paula Peck’s 1970 The Art of Fine Baking. I liked to think that the addition of espresso coffee made it mine. Click here to read "The Latest From France: The Eloquent Dollar," November 1983.

***

My Dinners with André

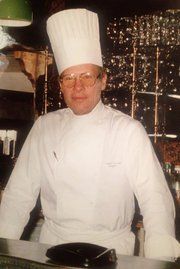

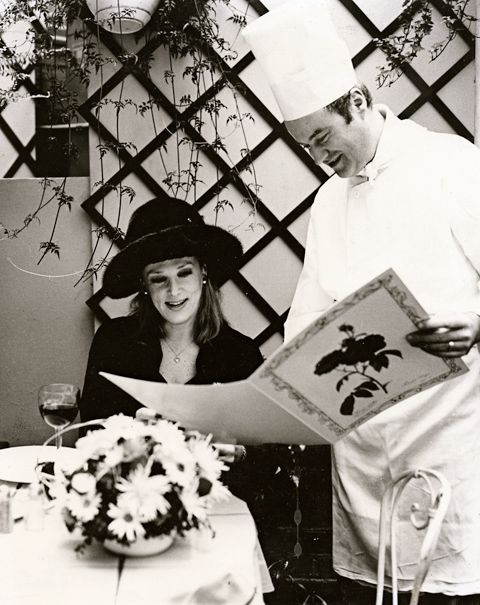

Chef-patron André Soltner discusses the menu with the no longer anonymous restaurant critic.

“He is the John Wayne of beurre blanc, defending the fort long after the rebels have hoisted the flag of radicchio,” I wrote in ‘My Dinners with André,’ in 1993. “The one pure chef, fearless in his conviction, with a certain naïveté. André Soltner, ruler of a tiny world on 50th Street, in a dollhouse castle 18 feet wide by 100 feet long. Lutèce, frozen in amber. To hurt him would be sacrilege – he is that honorable, genuinely loved and respected. He is simply what he is, no apology, no pretension, proud of his faith, though you might call it stubbornness. Sirio may call a dozen customers every morning and invite them for lunch, but André has never called one.

“Soltner has rarely strayed from the kitchen (‘just four nights in 30 years,’), unlike the gallivanting playboys of the American range and the Bocuse mileage-plus gang. ‘We are cooks, not ambassadors,’ he says. There are no Technicolor drawings in his sauces, no pyramids or flying buttresses on his plates. ‘Cook means what it means – to cook the food, not to architect it.’

“In a world of so few eternal verities, there is Lutèce. The neighbors change. New, gaudy awnings confuse. But there it is, the two steps down to the unassuming beige door, circa February 16, 1961. Madame Simone tucked into her cloistered crib, tracking the bills on (shocking twentieth-century touch) a small computer. For eighteen years, Pierre Autret has polished the small zinc bar below that very same street sign, PLACE DE FURSTENBERG. If you’ve loved Lutèce forever, the bar is a charming cranny. Without stardust in your eyes, it may seem cramped and shabby. Past the scrawny Pullman kitchen with its slit of a pass-through, into the parlor with its luxury of space. Refreshed each summer, with or without wallpaper, always the same.

“And into the trellised garden, where affection and expectation refract the daylight. Always, the same. The roses, pink tonight in a skinny silver pitcher. The famous Redouté print of the rose on the menu, a museum piece with its foie gras en brioche, the venerable mousse of duck with juniper berries, that ancient relic of the sixties mignon de boeuf en feuilleté – Beef Wellington to you – a menu revised not with the season but when the supply is exhausted.

“But that’s scarcely a felony. The listing is meant only to give first-timers something to hang on to, a strap on the subway as they hurtle toward dinner in what has been America’s most celebrated restaurant for decades. Habitués never see a menu. They eat the plats du jour.

“From the day in 1972 when founder Andre Surmain sailed his own boat across the Atlantic to Majorca in a fit of mid-life crisis, leaving the chef behind to buy him out, Soltner began emerging from the kitchen to make the dining room rotation. Smiling, eyes tilted up at the corner, he stands, one hand on his hip, in his laundry-issue whites – no custom order, no embroidery. ‘There are chefs working six weeks, and they must wear their name. Not me. I don’t need it. People know me anyway.’ He takes the order.

***

“If you grew up at Lutèce, and if your knees whimper sometimes, too, you may remember when the $8.50 lunch shocked the bourgeoisie. Likely, you noticed the gentle evolution in Soltner’s cooking. The light sauces, the less-cooked fish, the vegetable terrine held together with its own juices, the subtle creep of cilantro. ‘The products today are 1,000 percent better than twenty years ago,’ he will say. Forget the outsize plates. Not here. No chewy bread, no nutty grains. The roll is crustier now but bland. And though many of us, wallowing in our town’s gastromillenium, are tougher to thrill these days, there are thrills here. And many quiet pleasures.

“Sometimes it is simplicity that stuns. A perfect little chicken in a crackling mantle. A buttery pastry with fromage blanc and perfect squares of bacon on the tarte flambée. Thin cutlets of sweetbread, nattily crumbed and sautéed. Creamy layers of potatoes in a gratin dauphinois. The special tang of salmon lightly smoked over apple peels and applewood (brought green from the weekend house in Hunter every Monday).

“Entrées are a roll call of grand-mère’s cooking, the robust bistro fare I once saluted, provoking anguished outcries from the chef: ‘Lutèce is not a bistro.’ But the juicy veal shank (presented on the haunch), amazingly moist rabbit under a boa of root vegetables, and baked lamb with onions and potatoes are surely Alsatian home cooking. Earthy, like the tarts he gives away. ‘I cannot charge for them. It’s not Lutèce food. But the customers love it more than caviar.’

“My affair with Lutèce mirrors scenes from a long marriage. The first storm of passion. The deepening of love. Affectionate familiarity. A certain ennui. The seven-year itch. Irritation at the other’s inability to be anything but what he is. And now, admiration and tenderness for exactly that.” Click here to read My Dinners with André," September 1993.

***

This began as memories of Andre Surmain and it’s drifted into memories of Lutèce. I like to imagine there was a blonde brewing his porridge in the days before Surmain died at 97 in his home in St. Paul en Foret in the South of France. I’d like to think there was my chocolate velvet too.

More BITES You Might Savor...

Opry City Stage Le Coucou Eleven Madison Park