September 19, 2016 |

BITE: My Journal

Vintage Insatiable: How We Ate

When I started eating professionally in 1968, many affluent New Yorkers preferred canned peas.

As George Eliot observed while waiting for dessert: “It is hard to live up to our own eloquence and keep pace with winged words, while we are treading the solid earth and are liable to heavy dining.” That has inspired me to look back to the beginning…to the days before New Yorkers fell in love with food. Foodies were few (and not yet identified in the Oxford Dictionary), and we lived in a town where even the affluent liked their lamb chops well done and their peas from cans.

***

Papa Soulé Loves You

Henri Soulé was intimidating until I discovered that he loved publicity and tripes.

June 13, 1965. La Côte Basque Countdown: cinq, quatre, trois, deux…What a mess! In quenelles-de-brochet-eating circles, it was like the return to the concert stage of Vladimir Horowitz. Henri Soulé was making his historic comeback to La Côte Basque.

Showman, snob, perfectionist, martinet, con man, wooer and wooed master of haute cuisine, Henri Soulé, "greatest living restaurateur," recently reopened a kind of defrilled, discount annex to Le Pavillon, rated by most serious eaters as "the best French restaurant in America" and, by a hyperbolic few, "the only French restaurant in America."

La Côte Basque was Soulé's creation. It was his personal charity drive, a contribution to illicit romance. Or as he said: "La Côte Basque is Le Pavillon pour les pauvres, my Pavillon for the poor." And, "The Pavillon is elegant. The Côte Basque is amusing. Some people may find it quite convenient that Henri Soulé has two restaurants in Manhattan. A man may take his wife to Côte Basque and the other lady to Pavillon."

Pierre Franey came to America to work under Soulé at the French Pavillon in the 1939 World’s Fair.

From the moment it opened in 1958, La Côte Basque had been a spectacular success. Then, in a 1962 huff over what he called "insubordination by the waiters," Soulé locked the door. When the new owners of another legendary French restaurant, Chambord, offered to buy, Soulé was ready.

It thus became Le Café Chambord at La Côte Basque, an uneasy merger, doomed to an inelegant demise last July [1964] with unseemly talk of bankruptcy: left to rust, tarnish and mold.

At the age of 62, would Papa Soulé resume his schizophrenic gastronomic burden?

The gauntlet stings. It is a challenge. And after all there is a small matter of $260,000. Soulé sold La Côte Basque for that amount, "and most of the debt is still outstanding.” It is also a question of public service. All those jaded palates. New hope. A lift. A crack in the ennui of the middle-aged ladies with youth-frozen faces for whose ills there is no annual March of Dimes. Les girls. Les starving pauvres.

Papa Soulé loves you. CLICK here to read more.

***

Paley’s Preserve: The Ground Floor

Here’s William Paley at his most dashing, emerging from La Côte Basque.

November 11, 1968. The CBS Building is brown is beautiful is a sober monument to taste in the Manhattan grid of chrome, compromise and architecture by committee. Eero Saarinen drew it, but the details became a family affair. CBS president Frank Stanton and board chairman William Paley fussed over glass tints and elevator buttons. When it came to the family kitchen, it was clear from the start, one could not install a Chock Full o’Nuts in the nave of the cathedral.

Thus The Ground Floor is, above all, appropriately grand. It is slick, rich, calculated, spare, intimidating. It is Contemporary Wasp. You would hate to break open a roll for fear it would scatter unprogrammed crumbs. It is understatedly snob. There is no Bronx phone directory. Manhattan, of course, Brooklyn, yes. Even Queens. But no Bronx. You sense this slight to the Bronx is no accident.

Black Rock, the CBS headquarters, was Paley’s answer to the Seagram Building.

Nothing here is accident. Armies of interior designers have measured, computed, engineered. Even the sugar bowl is part of the statement. Granite plays against rosewood. Naked globes like upside down brandy snifters set in steel honeycombs make up patterns on the tablecloth. The house flower could only be…a red carnation, masculine in its upright rosewood casket. Shiny black matchbooks wear stark portraits by Irving Penn of nuts and clams. All elements measured, designed, engineered…no detail too minor. The quarter-round molding that borders the powder room carpet is gold…but not just plain gold…Florentine gold. Some draftsman spent maybe weeks at the drawing board calculating that touch.

The Ground Floor is a perfect room to end an affair in. The tables are far enough apart to announce the break in a firm voice, and the ambiance is stern enough to discourage sloppy emotionalism. CLICK here to read more.

***

La Côte Basque: The Quintessential Soulé Food

I would blush with envy as I was marched to nowhere past Babe Paley on the royal banquette.

November 25, 1968. Henri Soulé was the headmaster of America's prep school in haute cuisine, fabled Le Pavillon. Two generations of expatriate Frenchmen -- captains, waiters and sauciers -- did advanced studies in arrogance, ambiance and aspic with the mercurial master, then went on to stud the side streets of Manhattan with Pavillon offshoots: La Caravelle, La Grenouille, Lafayette, Le Mistral, a dozen more. Only one descendent was directly blessed. That was La Côte Basque.

In circles where eating is an art, an obsession, a sublimation, a status game, Soulé was the recognized master. It was only after he died while in a rage of pride and stubbornness (the fatal union snarl) that another dimension was revealed: Henri Soulé the lover. A fat man with pasty face, owl eyes, unnatural grace, this romantic hero! Many had assumed and some had written that the ubiquitous Mme. Henriette silently toting l'addition at the Pavillon cashbox was Mme. Soulé. But non.

Now, from the darker shores of Bayonne came the wife who had refused to suffer la vie Manhattan. She came to claim her inheritance. Secretly bohemian in life, strictly bourgeois in death, this Henri. Le Pavillon went to the highest bidders. But sentiment was served with the purchase of Côte Basque by Henriette. "I wish to keep the name of Henri alive," she said.

Only she is permitted to invoke the magic of the Soulé name.

It is there, on the canopy. The Pavillon spirit is there too. Not merely in the cellar with its half share of the Soulé wine hoard. Not only in the food which can rise to Pavillon hautesse. It is in the air. Electricity. Drama. A tension, as if something special were about to happen, not just another dreary duck in orange sauce, but the original duck in the quintessential orange sauce. CLICK here to read more.

***

The Mafia Guide to Dining Out

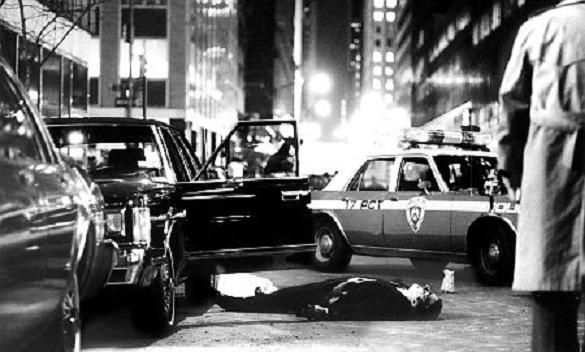

Paul Castellano put Sparks steakhouse on the Mafia map when he got shot at the curb after lunch.

April 7, 1969. The market is uneasy. Competition is fierce. The trust busters in blue are talking tough. Vito Genovese, chairman of the board of the oldest, richest, fattest, conglomerate of them all, is dead.

In tense times like these, the flow of corporate debate is primed by tranquilizing platters of Sicilian soul food: crusty rings of calamari, steaming bowls of zuppa di pesce, the purple splendor of a well-sauced eggplant.

The Carlo Giambino division had been eating up a storm at Villa Vivolo in Gravesend, Brooklyn...$40 a night, out of petty cash. Thomas (Tommy Ryan) Eboli, Vito’s acting underboss, and elder statesman Michele (Mike) Miranda...and sometimes titular executive pro tem Gerardo (Jerry) Catena...have been brooding about the rites of executive succession over espresso in the grubby Napoli e Notte Cafe at 165 Thompson Street. Why the Napoli e Notte? There’s nothing to eat but potato chips and pretzels. Nothing to look at but a very spiffy juke box, an unsmiling old lady in basic black, Pepe the poodle in bows of baby blue and a sign: “This is not a club. Don’t hang around.” Maybe the Genovese trustees are dieting. Tommy does have a bum heart. Mike has diabetes. And Jerry in the flesh is no Joe Namath.

Let these gourmandizing board meetings continue. What is good for the Mafia is good for gourmet country. The Mafia is widely advanced as “the Michelin Guide for Italian restaurants, and a three-star police raid is...a tribute to the excellence of the kitchen.

But is it? CLICK here to read more.

***

La Caravelle: Insult à La Carte

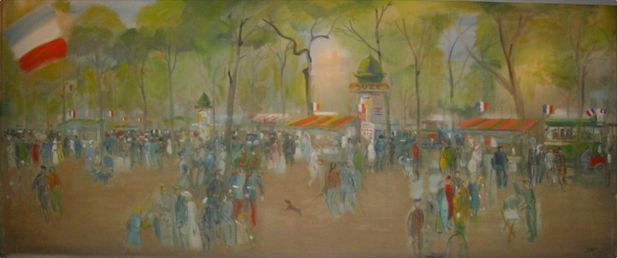

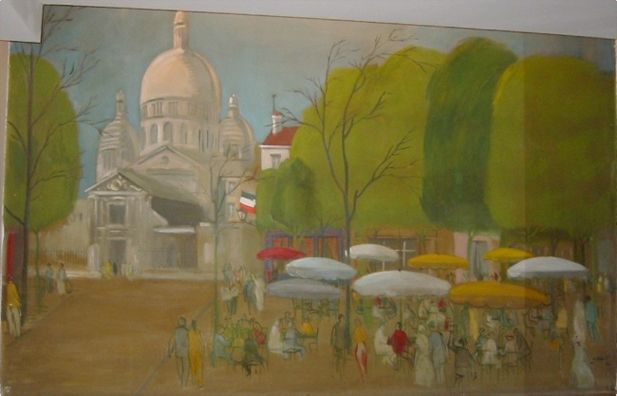

Jean Pagès colorful murals lined the walls at La Carvelle. Here, the Champs-Elysees Stamp Market.

May 19, 1969. Someday a gourmet anthropologist will do a thesis on the Manhattan culture's painful rites of passage. It will be called "Coming of Age on West 55th Street” or, “How the Ambitious Adolescent Attains Manhattan Manhood by Braving the Elegant Cruelty of Fashionable French Restaurant Snobisme."

Oh, sure, you can be a steakhouse snob and never starve. You can be king of the clan at your neighborhood chop-suey boite. You can swing your weight around among the potato latkes at Ratner's. But your tribal standing soars the day you can crack a genuine welcome in the great stone faces that guard the door of La Caravelle. A few are born to snobisme…sipping milk from Baccarat crystal at Le Pavillon during holidays from Choate…or teething on the flatware at "21."

The Montmartre Basilica by Pagès on the wall at La Caravelle in the days when I dared Siberia.

But to the rest of us -- expatriates from the provinces, escapees from Erasmus High and Gary, Indiana -- there is the exquisite torture, the terror of the unknown. Why do we endure it? Why do we pursue it? Why do we perform these daily exercises in masochism? Rejection must be some kind of basic human need. The French are masters of the fine art. And New Yorkers are the quintessential victims.

New York is a mecca for masochists. It is the Atlantis of our masochistic fantasies. How could we live anywhere else? We thrive on discomfort, frustration and scorn. Unpolluted air would shrivel our lungs…our muscles would atrophy if we did not have our daily leaps to avoid the doggy doo…our psyches would be scarred if a cabby opened a door or a waiter said, to an untitled stranger, "I don't recommend the plat du jour, Monsieur; the veal is somewhat dry."

Clammy with fear (and hope) of anticipated rejection, we phone La Caravelle to reserve a table. Preferably a day in advance. Or, aggressively, under a borrowed title: A table at one o'clock for the Princess Kiki de Guinzberg. Not that such tactics always work. Friends who phoned Thursday for Saturday lunch were sternly informed: "We don't know if we will have a table on Saturday." Click here to read more.

***

More BITES You Might Savor...

Save

Save

Save

Save