January 29, 2018 |

BITE: My Journal

Paul Bocuse led a merry band of chefs out of their kitchens.

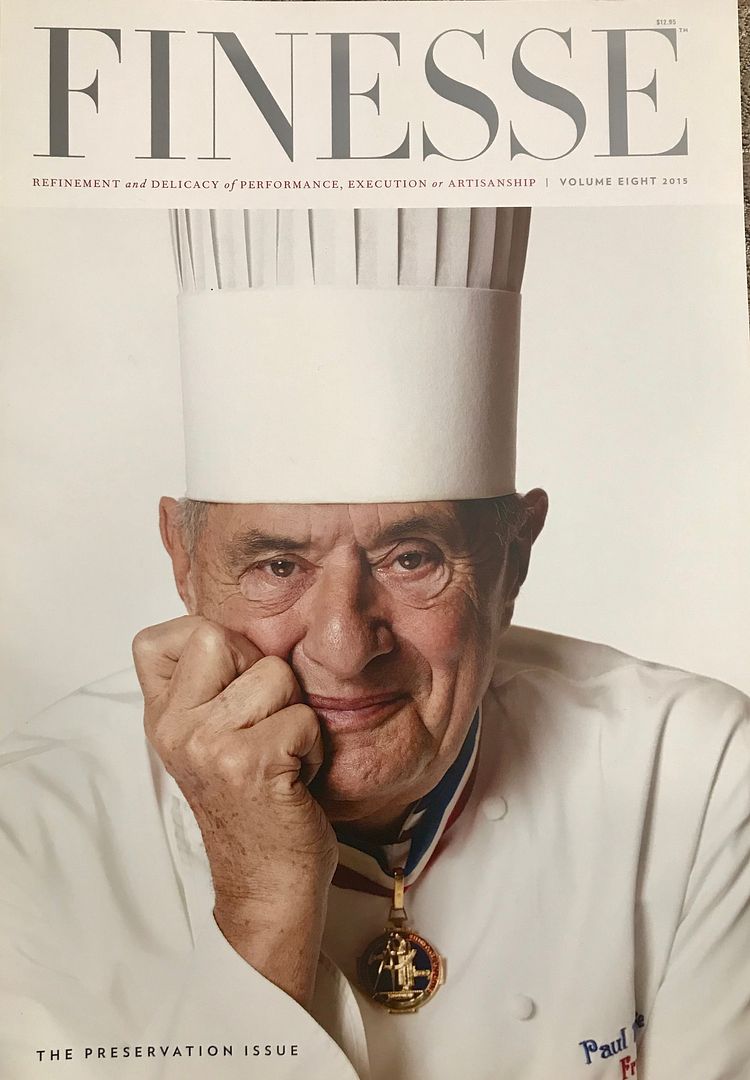

Remembering Paul Bocuse

I must admit I was not the early foodie who discovered Paul Bocuse and company lightening sauces and simplifying classic French cooking in 1973. My husband Don and I were among the early sybarites and embryonic gourmands exploring truffle fields abroad, shipping crates of flavored mustards home from Fauchon, and staggering away from our first three-star Michelin meal at Le Pyramide, also known as Chez Point, determined to find a way to finance as much similar debauchery as possible.

Publicist Yanou Collart decides to dress the chefs as artists.

No, it was Raymond Sokolov at the Times who first wrote about The Young Turks of France. And it was Craig Claiborne, introduced by me to Yanou Collart, the hyper-connected spokeswoman for the Grand Cuisine Française, who first got to celebrate the ambitious chef’s signature sea bass stuffed with lobster mousse and wrapped in pastry scales and fins.

My guy and I were actually eating the Troisgros brothers’ shockingly revolutionary cooked-on-one-side-for three-and-a-half-seconds salmon in sorrel sauce when Gault and Millau gave it a name. Nouvelle Cuisine. Plates got bigger. Portions got smaller. What was raw got cooked. What had been cooked was now raw.

Paul Bocuse Pours his Beaujolais at The Dinner of the Century

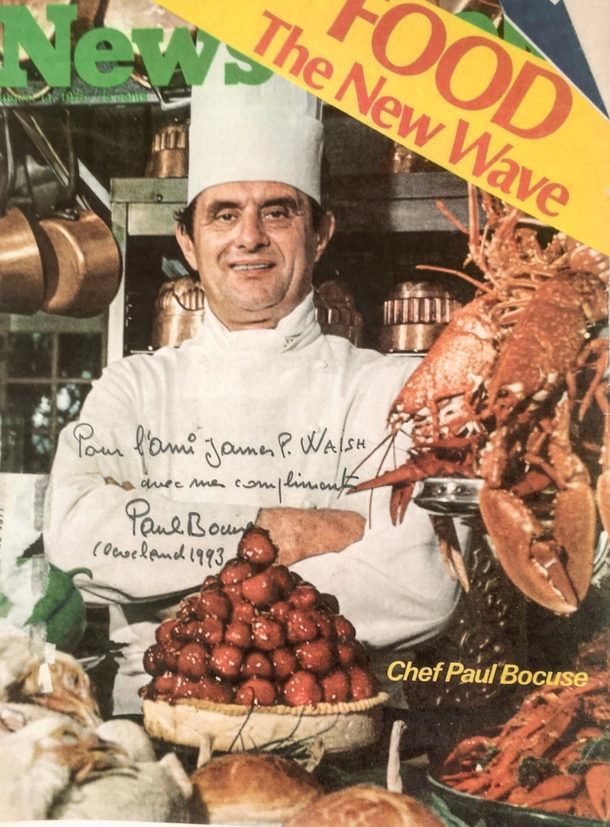

Newsweek discovers that food is the new wave in August 1975.

Soon I was in the middle of the knockdown struggle for supremacy between wine merchant William Sokolin and the Wine and Food Society’s oenophilic young Macbeth, Roger Yaseen, for control of Paul Bocuse’s proposed “Dinner of the Century” at the Four Seasons to promote the Bocuse Beaujolais.

“Glory and three stars in the Guide Michelin” are not necessarily convertible into big-time loot,” I wrote, and “one day the great chef of Lyon realized he wasn’t going to be as rich as the man who put cassoulet into cans.” About that time, Melvin Master, an ambitious young wine merchant, moved from London to Aix-en-Provence.

On Madison Avenue just below 34th Street, William Sokolin longed to find something more meaningful than discount booze. When Master offered Sokolin an exclusive franchise on Bocuse wines for most of the Eastern Seaboard, Sokolin promised to love, honor and advertise. Fourteen hundred responses came in when he advertised that the chef has agreed to cook a dinner in New York City for ten. It was chaos, panic, doomsday.

Click here to read my 1973 report on the “Dinner of the Century: Trial by Pig’s Bladder”

***

Nobody Know the Truffles I’ve Seen

The chef with his instinct for branding welcomes you to his restaurant in Collonges.

“Press junkets and free meals are strictly forbidden for New York magazine critics and contributing editors,” I confessed some months later in my column. But there was no way I could refuse the totally elegant hustle Collart proposed next. All over France, chefs were hoarding the fattest duck livers, she said. Ten of America’s greatest writers would be invited to the grand bouffe of all grand bouffes, criss-crossing France from one foie gras to another at three- and two-star Michelin restaurants in the private jets of Moët et Chandon champagne and Hennessy Cognac.

Yanou asked me for a list of literary giants. I suggested Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, John Updike, Philip Roth, William Styron, Kurt Vonnegut, Gore Vidal. I thrilled imagining the bon mots we would exchange over our Dom Pérignon. When I boarded our flight to Paris and discovered that Al Goldstein of Screw and Bob Guccione’s sister (“I only drink diet Coke.) were standing in for Updike and Roth, my hopes for elevated discourse faded. Danny Kaye would meet us in Paris, I was told. What did that portend? I wondered.

Bocuse introduces our champagne-addled team to his catering hall where caviar comes in two-kilo tins.

Yanou divvied us up between planes with different dining assignments, making sure that both Danny and I were in her entourage. Our little jet wasn’t scheduled to visit Bocuse, but the chef called Yanou and insisted we must come by for lunch in his catering hall, L’Abbaye de Collonges. There, I recall confronting a two-kilo container of caviar, while my mates joined the chef singing the National anthems of France, Britain and America. Click here to read: “Nobody knows the Truffles I’ve Seen.”

When Bocuse arrived in New York, he often headed directly to Le Cirque to check in with Sirio Maccione.

In my best but admittedly limited French, I had chastised Bocuse for not insisting that female wine writers be included in his first New York dinner. He had agreed to return and cook a second feast “just for women.” I could have tried to explain how that was equally insulting. Instead, I agreed to invite a sprinkling of super press and women of great accomplishment…”but they must all be women somehow involved with food, as cooks or epicures.”

Alas, that eliminated Gloria Steinem. Even though Gloria had confessed to bingeing on Häagen-Dazs, she was clearly not a gourmand. I dismissed Post publisher Dorothy Schiff because I knew she fed even her most lofty guests sandwiches from the deli. In the next few days I made 100 enemies and offended dearest friends.

I didn’t know many of the Immortals at the Dinner for Women. Just Julia Child. But no one said “no.”

I was stunned by the company I had collected. Lillian Hellman in a filmy caftan told a Dorothy Parker story about the erection of a snapping turtle. Sculptor Louise Nevelson confided to Pauline Trigère that she is normally naked under her folk costume. Times society writer Charlotte Curtis wore a sweater under her dress. (Was that meant to express journalistic integrity?) Bess Myerson’s costume was not memorable but it didn’t matter, since her posture and body were so perfect. Soprano Margaret Tynes was supposed to be in bed, resting to standby for Salome at the Met, but she came anyway. So did Sally Quinn.

I only knew Julia Child and Danny’s daughter, Dena Kaye, who lived on West End Avenue across from me, but it didn’t seem to matter. Paul Bocuse, assisted by Jean Troisgros and Gaston Lenôtre, cooking a dinner for women at the Four Seasons, was apparently an irresistible invitation.

The chefs had arrived in a frenzy of indignation. The veal rump had been seized by Customs. Also a haunch of venison, a hank of Lyonnaise sausage, four perfect chickens and a stash of fat French cream. The Customs agent questioned what looked like little black golf balls in a package under the chef’s arm. Paul flashed them quickly. “Just chocolates,” he said.

“Where can I find a serious rump of veal?” he wanted to know.

Friends of Bocuse were asked to put in calls to their senators to protest. Click here to read “More Confessions of a Sensualist: The Dinner for Women.” Discover how we made do with crayfish tails, truffle ragout, and bass baked in seaweed, all washed down with Bocuse Beaujolais.

***

Stalking the Moveable Feast

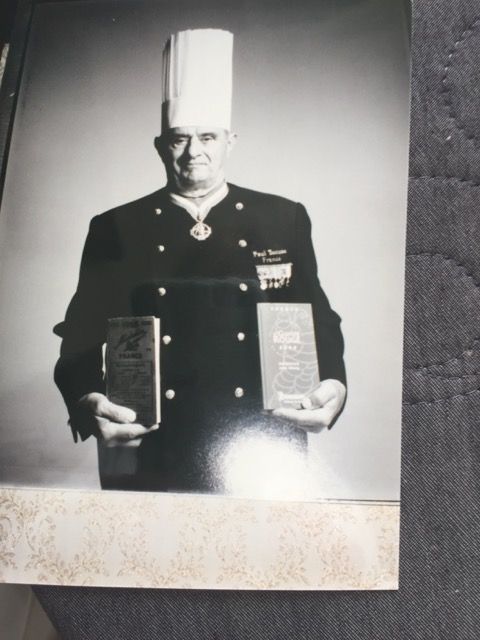

French president Giscard d’Estaing awarded the French Legion of Honor to Bocuse in 1975.

October 17, 1977. I am back in France on the magazine’s dime. “It is the season for great mushrooms, game and truffles,” I wrote. “’Prices are up,” I was sad to report. “Dinner in the celebrated maisons will run $100 for two.” Amazingly, I found most of the young turks now middle-aged. The peripatetic Bocuse had put Roger Jalous in charge of the kitchen, and given the dining room reins to three strong women -- his mother, his wife and his daughter.

***

Murder in the Kitchen

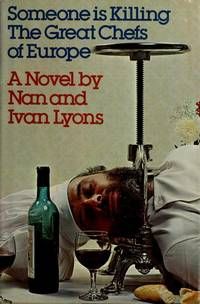

Since Bocuse was hired to consult for the movie, Who’s Killing the Great Chefs, I decided to consult too.

Paul Bocuse had been signed as a consultant on the set of Someone is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe. It was 1978. A scene was being filmed in the grungy subterranean kitchen of Lapérouse. I’d been summoned by Yanou to document this frolic of gastronomic crime.

Jacqueline Bisset assures me she needs no coaching. “I’m a cook myself,” she tells me. I very delicately suggest that the correct way to hold a wine glass is by the stem, not the bowl. She does not seem offended. Across town Yanou is alarmed. “They are asking Paul Bocuse to prepare a bombe for the press on Friday and this morning they’re switching it from raspberry to chocolate.” She is clearly offended.

“Paul is not a coat hanger you take down whenever you please. If they’d done the meal as it was written, it would have been a Mel Brooks movie. Imagine. They were serving woodcock with orange and ginger. Poached oysters béchamel – do you believe it?” Mlle. Collart picks up the phone and snaps: “Well, is it raspberry or chocolate?”

Why would anyone kill a great chef? I ask myself as I race off for last-minute personal shopping at Fauchon. More likely a chef might want to kill a restaurant critic, I mused. That would be fast and quite too easy. Click here to read “Murder in the Kitchen.”

***

Pie in the Sky

It didn’t matter what Bocuse and pals created for the TWA premier flight to London. It was too rough to eat.

It’s true that Bocuse did not have to reach far to find an insult for women. He clearly had little respect for female cooks. “Don’t you ever get bored with the repetitious honk of Paul Bocuse?” friends were asking by 1978. They seemed to think I might be weary of all that sauce choron, the endless parade of goat cheese, the chickens wrapped in pigs’ bladders.

“How could I be?” As if one could be bored with the sunset or a ripe pear. So when TWA announced it would inaugurate its new Tristar flight to London in June 1978 with three chefs cooking aloft – Paul, Roger Vergé and Gaston Lenôtre -- I couldn’t say no and paid my $313 one way.

I imagined Bocuse – truffles bouncing in the turbulence – wrapping the entire first-class cabin in a flaky pastry croûte. I saw myself blissed to sleep in a rain of petits four and bon bons, scattered by Gaston. Yanou Collart was there to be sure each straw stuck in each little button of goat cheese has been snipped to fit into the food cart shelves.

“In book sales, cooking runs ahead of sex and sex runs ahead of the Bible,” TWA vice-president Don Casey pointed out. “I can’t explain it. I’m not a food person.” But I am a food person. So I didn’t argue. It would be fog vs. frog. Click here to read "Pie in the Sky."

The chef honored his history with brilliant portraits all in a row in the garden.

Given the speed and efficiency of France’s TGV train, getting to Lyon for lunch with Paul Bocuse is a cinch compared to inching your way to Easthampton in time for dinner Friday evening. The Road Food Warrior and I have been invited to a lunch arranged for Jean Luc Colombo – his big supple Cornas is the new Rhone wine sensation. We are joining Jean Luc, his wife and their pals at the three star house of Paul Bocuse, Collonges au Mont d’Or, north of Lyon.

My guy Steven Richter took this photo of me with Paul the last time I visited him in Collonges.

I can’t recall how long it’s been since I made this pilgrimage. Decades, for sure. The invitation to lunch, instigated by that irresistibly charming publicist and fantasy-enabler, Yanou Collart, is irresistible. That’s why my guy and I are committing almost $650 to get to Collonges – for the speedy two-hour train ride and connecting taxis to the small town Bocuse taught us to spell. I longed for this connection as a link to the past – my own forty years as a restaurant critic - and perhaps even as a goodbye. Bocuse’s family had said he wasn’t well enough to fly when we invited him to be honored at Citymeals on Wheels June event, La Crème de la Crème.

He stood with his wife and daughter as we were served all the classics on dishes with his name.

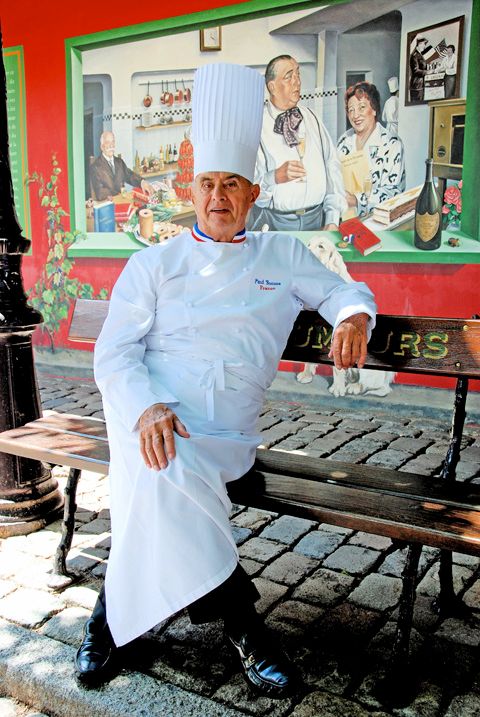

Once the taxi from Lyon has delivered us, we’re greeted by an assistant who leads us into the courtyard where Paul sits surrounded by a series of painted murals, his glorious “Rue des Grand Chefs.” He stands for a hug, thick in his whites and long apron…and slow. The son, grandson and great grandson in a line of cooks dating to the 17th century, he is in his 42nd year of three Michelin stars. And it looks like he has never stopped embellishing the once simple country house where he started cooking with his father.

As usual the chickens were cooked in front of a fire and presented before serving.

There are brass plaques underfoot commemorating friends who have died as you walk toward the door, articles and accolades everywhere. The fanciful red and green paint job gives the expanded building an Alpine look, a hint of Disneyland. You can laugh at the paintings on the terrace, but they are fabulous. In the first, we see Carème with his patron Napoleon, Empress Josephine at his side, palming an American Express card.

Of course, we’ll have cheese. No wonder lunch stretches beyond dinner.

Paul points it out in case you missed that card. “Napoleon is broke and he pays with the credit card.”

Click here to read Paul Bocuse: The Lion in Winter. July 2008

The Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park celebrated their new Bocuse dining room with this logo.

February 15, 2017. I’d committed to celebrate Paul Bocuse and the launch of The Bocuse Restaurant at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park. The homage began with chocolate birthday cake, its many tiers and towers frosted by the students for the great chef’s 87th birthday. And it went on to diminutive steak tartare sliders with cocktails, and foie gras in the shape of a peach.

The CIA audience cheered when Bocuse walked onto the stage with Jean-Georges, Daniel and son Jerome.

It was a rare day for the students at CIA. Assembled in the auditorium, they gasped and screamed and cheered when Paul Bocuse walked onto the stage in his whites with his son Jerome, to join a panel of Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Thomas Keller and Daniel Boulud on the state of their art and the future of food. “You are the future,” everyone on the panel told the students. Then the tiered and towered birthday cake was unveiled and pastry students rolled in tables with rows of individual domes enrobed in chocolate for the audience.

Bocuse created this pastry-wrapped soup to celebrate his Chevalier award.

Inspired perhaps by France’s rakish tradition of smashing the head of a Champagne bottle with a sword, CIA president Dr. Tim Ryan signals the start of dinner by smashing the pastry dome off a giant replica of Bocuse’s iconic Black Truffle Soup VGE with two big spoons. The initials refer to Valery Giscard d’Estaing, the French President who invited Bocuse to accept the Légion d'honneur in 1975. Undertaking his own reception banquet, the chef created the now iconic broth, its toque of pastry and the small tureen with lion faces that he serves it in.

Two minutes before this photo at the CIA launch, Bocuse was grabbing my breasts. What else is new?

Give the guy his due. Bocuse understood branding before there was a word for it.

Click here to read Merci Bocuse: 1000 Tastes Are Just Enough